Last year, I published an article on a set of Coppergate-inspired clothing. In that article, I mentioned that the shoes and socks I was wearing with that outfit were not exactly what I had hoped to include. I remedied this not long after we took the photo set and so now I’d like to share the new items with you!

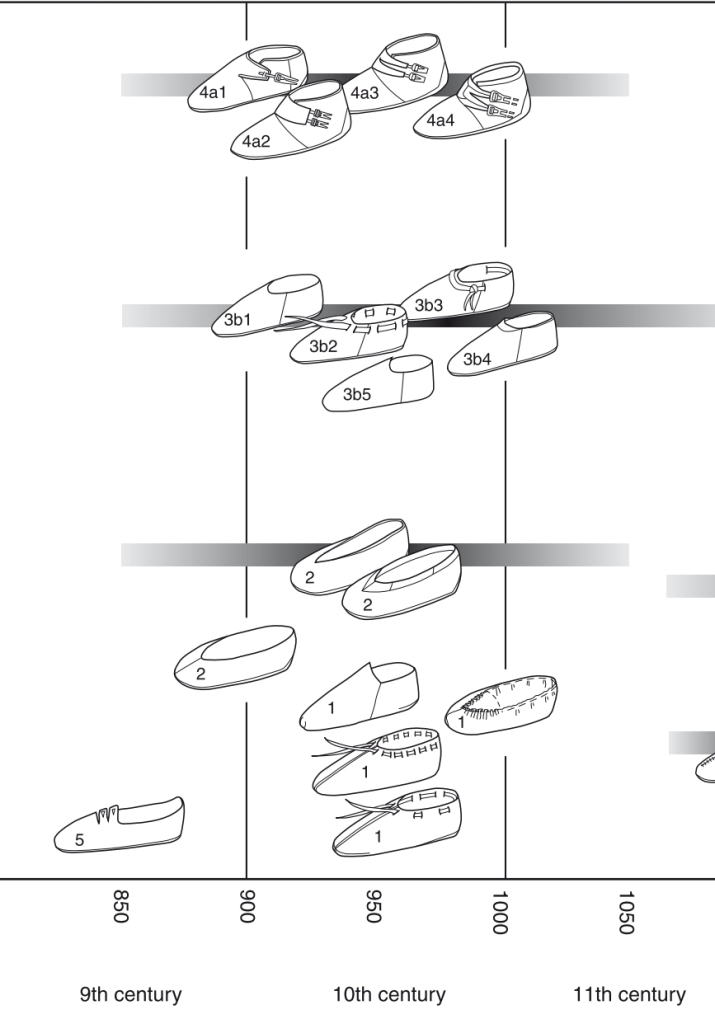

One-piece ankle-shoes, fastened with a single

toggle and flap (classified as Style 4a1)

These shoes were made for me by my friend Dean, who is a wonderful shoemaker. They’re entirely handsewn on maple sewing supports, with the purpose of making them as close to the original finds as possible.

Shoes with a single flap and toggle are

dated to c.930/5–c.975 AD in York, with seventeen examples from 16-22 Coppergate. Single examples were found in deposits each dating to the late 9th century and to the 11th century, but it does seem that this style saw its heyday in the mid 10th century. Shoes belonging to this style have been found at other VA sites in York and further afield. (Mould, Carlisle, & Cameron, 2003. p.3304.)

My shoes are made of soft calfskin uppers and thicker bovine leather for the soles. They have a decorative edge binding along the top edge made from goatskin, which is folded over and whipstitched down on the inside. This binding also serves to stiffen the fine leather of the uppers. To sew my shoes, Dean used a saddle stitch of a strong linen thread coated in shoemaker’s coad, a homemade blend of beeswax and birch tar. The most common stitching medium in the York shoes seems to have been animal fibre such as wool or leather thonging (MacGregor (1978), p.53), however, there is a find from Feasegate that appears to have been sewn with flax.

Something interesting you may notice about these shoes is that both the toggle flaps and the single seams in the uppers are on the inside of the shoe. You will likely have seen many reproductions of boots like these with the toggles on the outside, which might seem more logical. However, the examples of these shoes from York all fasten over the instep and when you put them on, it is indeed easier to fasten them that way!

The toggles are very simple T-shapes of leather, with a slit cut in the top of the T and the length being pulled through in order to roll the toggle itself. The toggles and the loops they go through are secured to the shoe in one of several ways, but the most common is also the most simple- they are threaded through a series of slits cut into the flaps and inner quarters of the shoe. The tension of the leather holds the straps in place, but this method also allows for the fit to be adjusted. (Mould, Carlisle and Cameron, 2003. pp. 3302.)

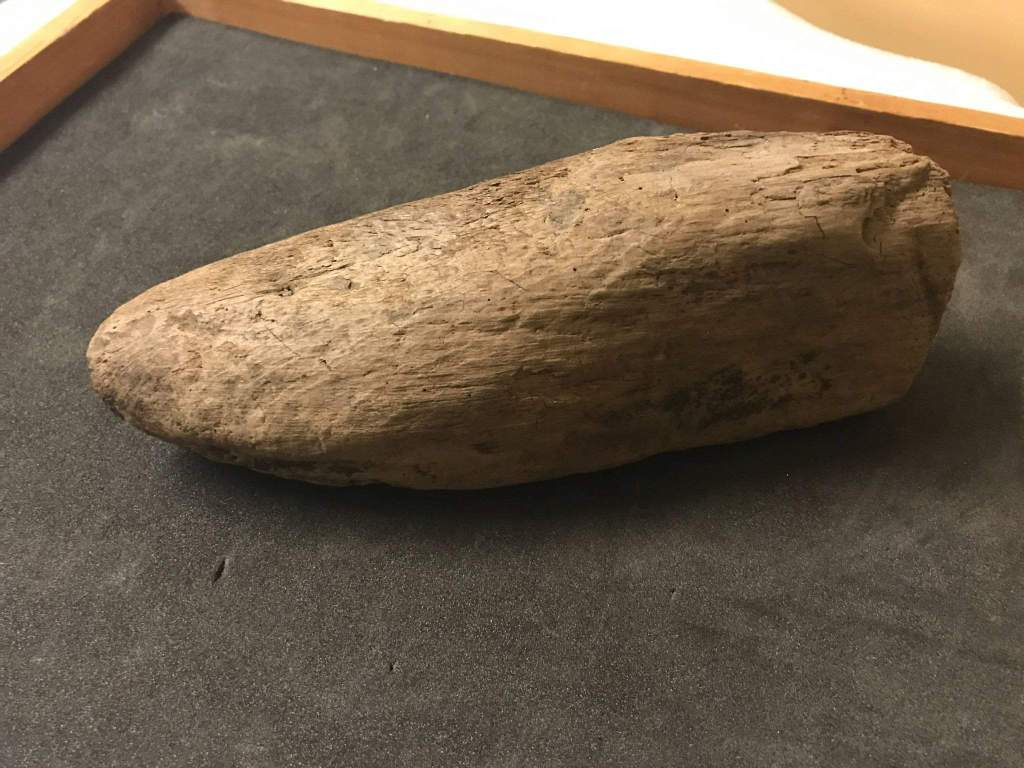

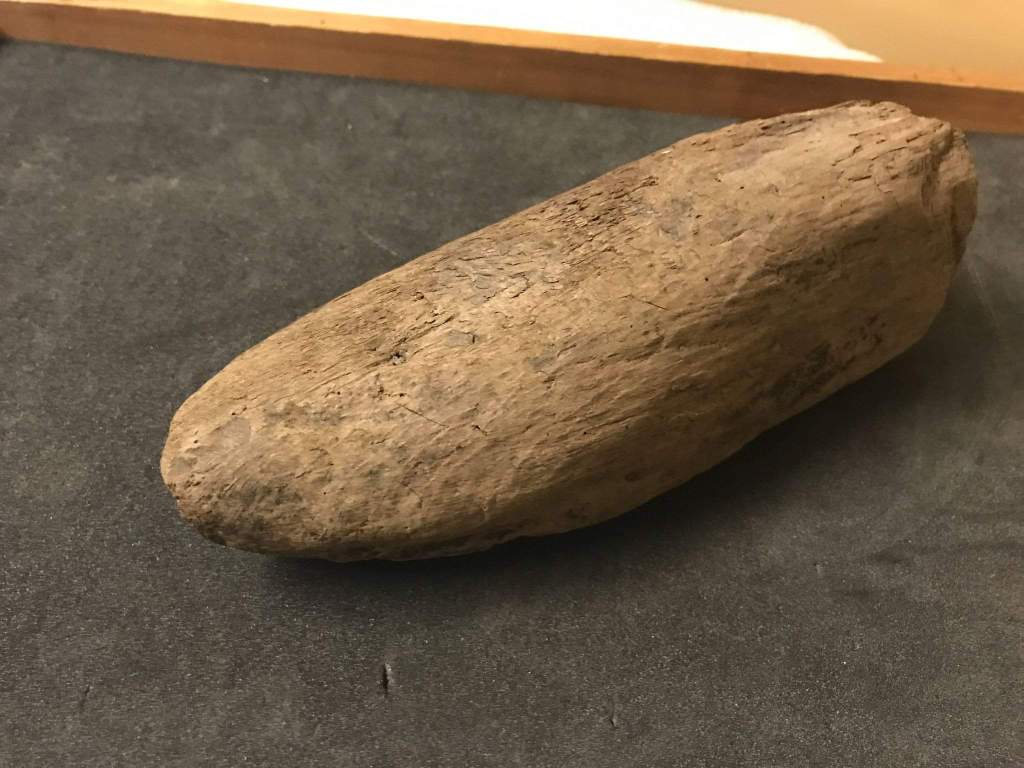

The last/support that Dean made my shoes on was based on a find from Lloyds Bank, item 494. (MacGregor, 1982. pp. 144.) The original dated to the 10th century and was made from alder, whereas Dean’s is made of maple. I thought it was interesting to note that item 494 still had pieces of leather attached to the wood with iron nails, but probably not from shoes. It appears that there was an attempt to build up the surface of the last using these pieces of leather, either from wear and tear from use or indeed from being a little axe-happy in the initial shaping of the last.

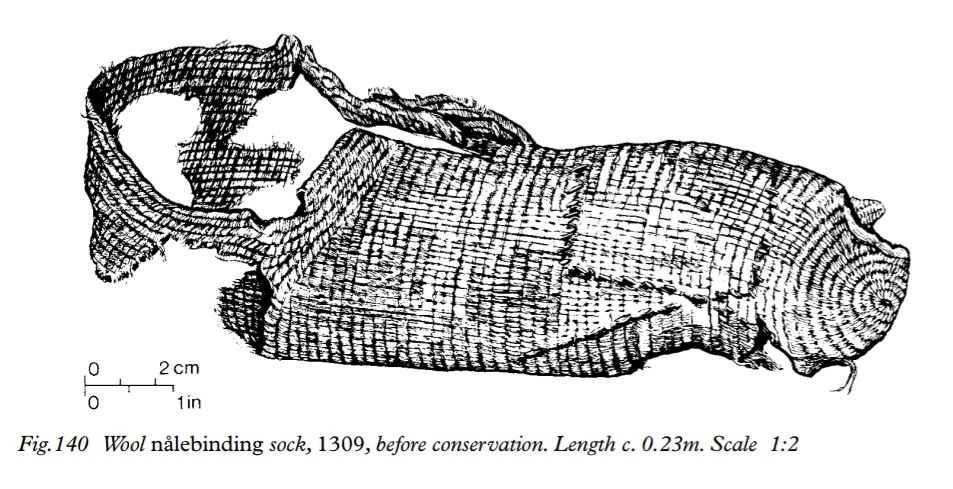

Woollen needlebound (nalbound) socks in York/Coppergate stitch. Based on item 1309 from 16-22 Coppergate (Period 4B.)

One of the most famous surviving textiles of Viking Age Britain: the York sock! For many readers, it will need no introduction. For those who are not familiar with it, I’ll briefly explain what needlebinding (or nalebinding or naalbinding) is and quite why this sock is so special.

Needlebinding is a technique for making cloth that only uses a single needle and lengths of yarn that have to be added as you go. It’s an ancient technique with examples being found dating back to the 3rd or 4th century AD in Sweden (though it could even have been practiced as far back as the Neolithic.) (Walton, 1989.) There are many different needlebinding stitches and each results in a slightly different texture, pattern, density and level of elasticity. Something that all needlebinding has in common is that it doesn’t unravel, unlike knitting or crochet.

At the time of its discovery, the York sock was the only example of needlebinding found in England. York/Coppergate stitch, the stitch the sock is worked in, was named after the sock and is described in needlebinding terminology as uu/ooo F2. The sock itself is in pretty good condition, with most of its structure remaining. It was made up of undyed S2Z plied wool yarn with a narrow band at the top of the sock being dyed with madder.

In my reconstruction, I chose to use a Shetland sock weight yarn from Highfield Textiles, a local wool producer from East Yorkshire. I hand-dyed the same yarn for the ankle band using madder, which resulted in a lovely rich orange-red. Like the original, my socks are slipper-style and don’t reach above the ankle. York stitch is also super stretchy, so when taken off, they tend to curl up- you can see this in the photos!

Footed short hose, inspired by various historical finds and fragment 1303 (Period 4B.)

The shape of these short hose is entirely speculative. Thunem (2018) gave a comprehensive overview of the topic of socks and hose in the Early Medieval period, which I highly recommend for further information. I made my first pair of these hose during the pandemic in a Zoom class taught by Astri Bryde and this pair is my second (with some alterations to improve personal fit.) As they are cut straight on the bias, they are not stretchy and so are not as tightly-tailored as later Medieval hose.

They’re inspired by earlier finds like the 2nd century stockings from Martres-de-Veyres, later finds like the 14th century Bocksten footed hose and of course the VA fragments from Haithabu Harbour. They’re made in two pieces, a long leg piece and a curved foot piece with the seam going under the foot (like the Skjoldehamn socks!) You might think that this would be uncomfortable, but it’s really not that noticeable and definitely not uncomfortable.

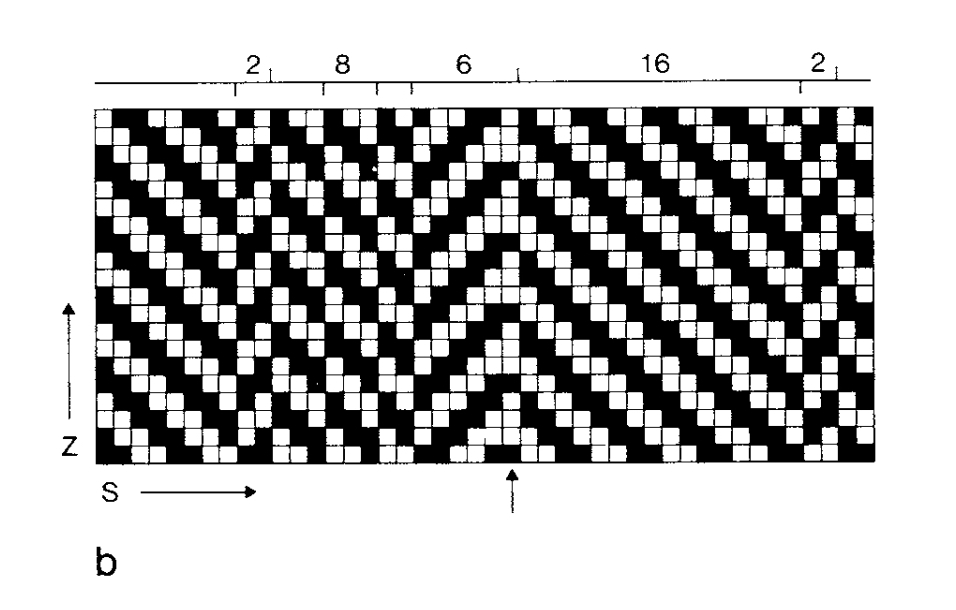

I chose to make these hose from a woven British tweed cloth, inspired by fragment 1303 from Coppergate. This fragment of 2/2 chevron twill was found in association with the naalbound York sock 1309. It is described in Walton (1989) as:

“Fragment, 140 x 60mm, of 2/2 chevron twill with dark combed warp and lighter non-combed weft, and selvedge. (…) Warp hairy fleece type, naturally pigmented, weft hairy medium fleece type, not pigmented. No dye detected. The softer weft has become heavily matted in places. The side of the fragment opposite the selvedge has been cut, there are two overstitches, possibly part of a hem at right-angles to the selvedge: sewing yarn plied wool, S2Z (…)”

Fabric woven in two shades is uncommon in the Viking Age generally, not just in York. Using two different shades for the warp and weft will make the pattern “pop” in a way that is less obvious when using one colour of yarn. Walton (1989) identifies 1303’s similarity to a fragment from Haithabu (thought to be a pair of hose!) and the lack of similar English finds lead her to conclude that 1303 was a foreign import. This idea is supported by the fact that 1303 was found in association with the York sock, also thought to be either a Scandinavian import or the handiwork of a Scandinavian settler.

I find it interesting that matting is mentioned, as I’ve only worn these hose twice and yet matting is visible underfoot and a little underneath the ties at the knee. This is to be expected with the friction, warmth and slight damp that comes with items worn on the feet.

The ties I used to hold up the hose were made in a hurry- they are thin braided cords made from fine naturally-pigmented brown wool yarn. Similar cords are found in 10th century levels at Coppergate, however they are generally cabled rather than plaited. Woven or tablet woven garters like the ones worn with later Medieval hose might well be another option in future.

The whole ensemble

Overall, I found this collection of garments comfortable and functional to wear. On both occasions, it was cold winter weather and provided I didn’t take them off to film a reel for Instagram (ahem), my feet were kept dry and well-insulated. I have worn the hose with socks underneath and without and naturally the combination was warmer. The seam underneath the sole of the foot did not affect my comfort and the hose didn’t slip down my leg once tied at the knee.

Being made to fit my feet, my shoes are extremely cosy and supportive. They are of course more comfortable on grass and earth than on concrete, but that is the case for all turnshoes. I am really won over by toggled shoes that fasten on the instep- I already have a pair with ties round the angles and these are just as comfy with a cooler silhouette.

If you’d like to see how this footwear looks as part of a complete outfit and also how they are put on, I made a Get Ready With Me video that features them on my Instagram.

References

MacGregor, A. (1978). Industry and commerce in Anglo-Scandinavian York. In: Hall, R. A. (Ed). Viking Age York and the North. York: Council for British Archaeology. pp.37-57.

MacGregor, A. (1982). Anglo-Scandinavian Finds from Lloyds Bank, Pavement, and Other Sites. York: York Archaeological Trust. pp.144-145.

Mould, Q., Carlisle, I. and Cameron, E. (2003). Leather and Leatherworking in Anglo-Scandinavian and Medieval York. York: York Archaeological Trust. pp.3185-3535.

Thunem, H. (2018). Viking Clothing: hose and socks. [Online]. Urd.priv.no. Last Updated: 5 March 2018. Available at: https://urd.priv.no/viking/hose.html#thunem-interpretation [Accessed 31 January 2023].

Walton, P. (1989). Textiles, Cordage and Raw Fibre from 16–22 Coppergate. York: York Archaeological Trust. PDF.

Bibliography and useful links

Highfield Textiles, the small business where I bought the yarn for my socks. https://www.facebook.com/highfieldtextiles

If you liked this article, please share it with your friends and follow my blog to get updates of my future work.

You can also buy me a coffee via Ko-fi if you really liked it! https://ko-fi.com/eoforwicproject