Or, Adventures In Wood Quay!

Location: Dyflin (Dublin), Ireland

Date: Mid to late 10th Century

Culture: Hiberno Scandinavian

Estimated Social Class: Free working woman

This Valentines Day wasn’t especially traditional, but it was one of my best ever. Due to Coronavirus nerfing many routes to Luxembourg from England, Eric and I had to fly via Dublin in order to see our family. We decided to make the most of it and stay for Valentines Day on the way back.

What did I want to do? I wanted to go to Wood Quay and pose in the cold in a quickly cobbled-together Dublin impression.

This outfit isn’t especially complex, as I could only take a small bag that would fit within my cabin luggage. That means no undertunic and no turnshoes- you can see my cowboy boots in later pictures. This set of gear is a work in progress and in future, I’ll be getting a few pairs of suitable shoes based on Dublin remains. (Note: if anyone has access to good publications on shoes from Viking Age Dublin, please hit me up!)

Wood Quay is a historic area of Dublin, only a stone’s throw away from bustling Temple Bar and the Ha’penny Bridge. It made headlines worldwide in the 1970s when the area was revealed to be an archaeological goldmine during the building of a new Dublin City Council headquarters. The story is actually fascinating and I can write a “For Dummies” article in future in folks are interested.

The short version, however, is that there was nationwide and international protest against the development, in order to first properly excavate the whole block of all its rich historical goodies. Dublin City Council ignored them and built their new civic offices on the site anyway, with excavations finishing in the March of 1981 (Wallace, 2016.)

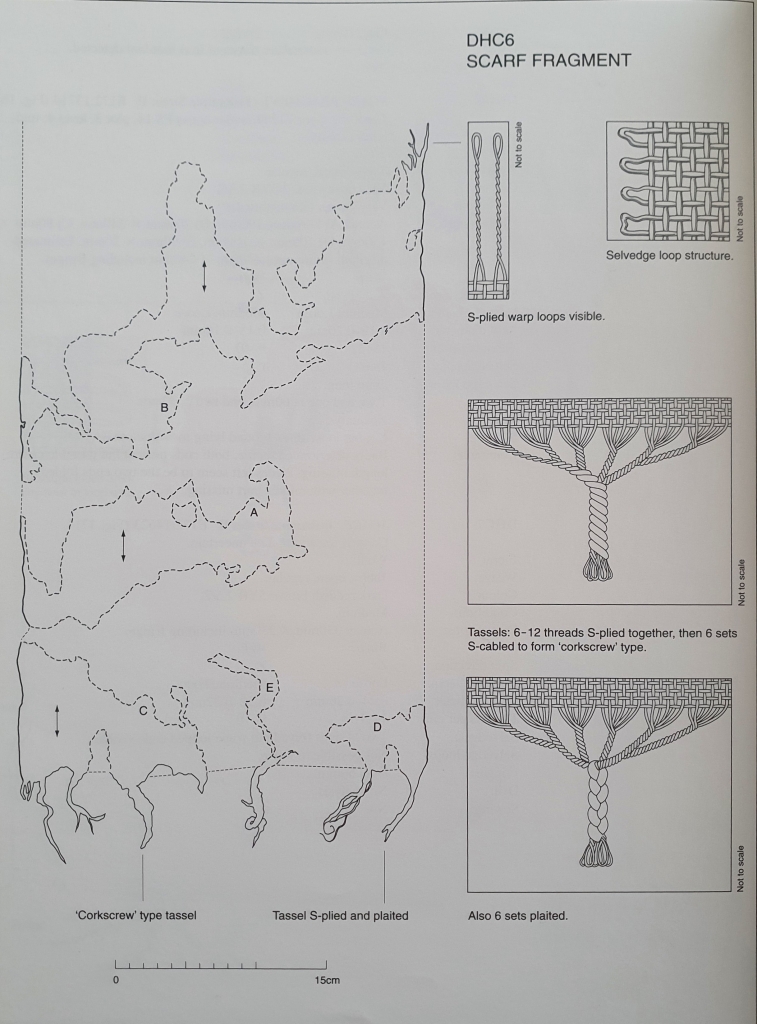

Headscarf based on fragment DHC6 (Fishamble Street)

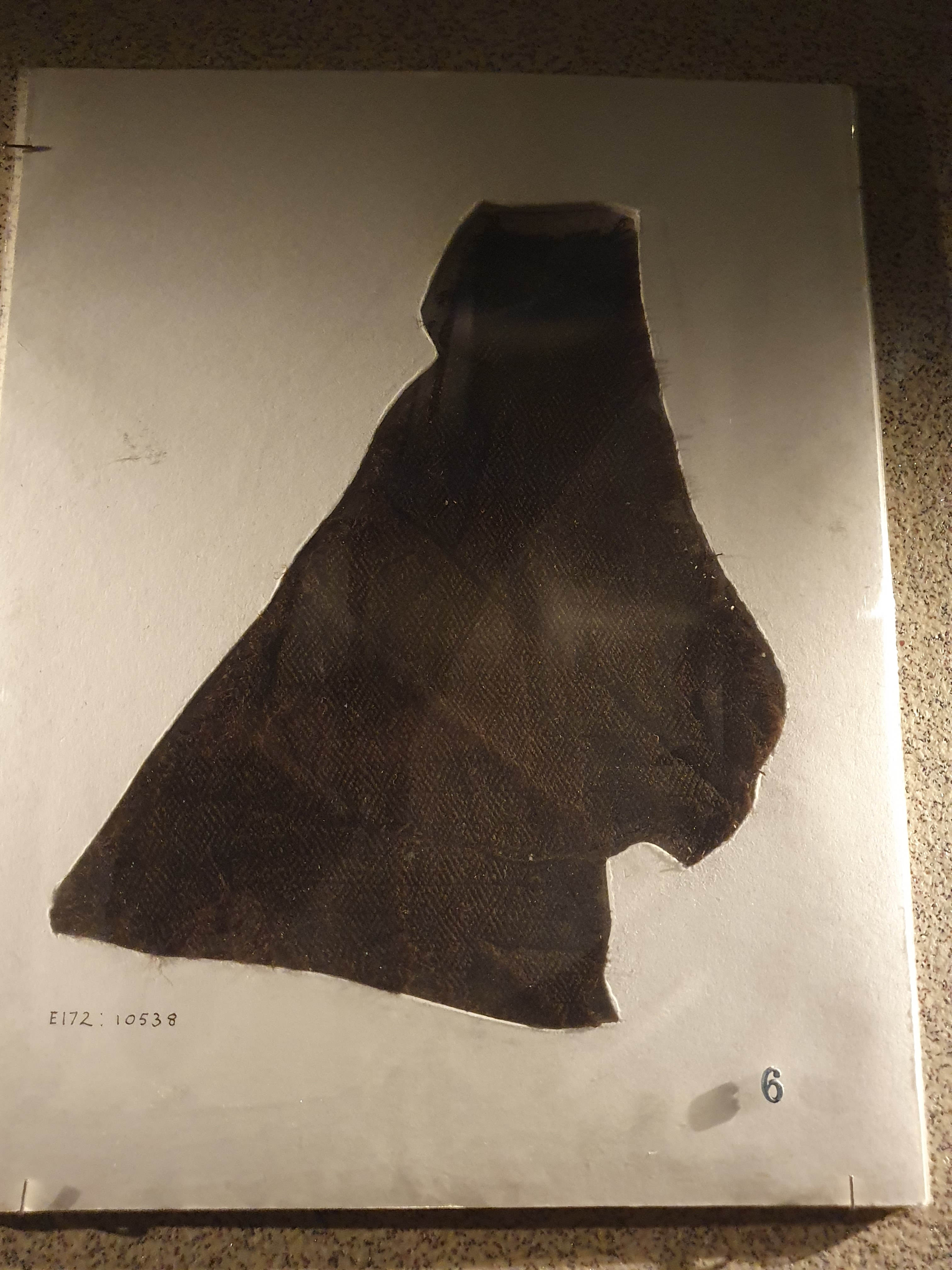

I’ve written about this piece before (my article about it can be read here.) It’s a plain weave woollen scarf, dyed with an exhaust woad bath over a naturally pale grey. It was found on Fishamble Street and dated to the mid 10th century. I tasselled the ends by hand and the dimensions of the scarf are based directly on the textile remains labelled DHC6, though my tassels are slightly simpler than the original.

I like to wear it by itself without a cap and with a simple woollen fillet (tablet woven), but it could easily be combined with other headbands and caps to give different looks. I tied my hair with a very simple finger loop braid- we don’t have any evidence that I know of for hair ties in the Viking Age, but simple cords, braids and thonging must have been used.

I imagine that a weakly dyed item of wool such as this could reasonably have been worn by an average city dweller wanting to keep up with trends. It isn’t a large item and so likely would not have carried the same prestige as the huge voluminous veils worn by queens and saints in manuscripts, however, it could have served to provide either some form of modesty or just fashion for the wearer. Wincott-Heckett (2003) suggests that these small tasselled scarves were of local production and so could indicate a local fashion.

Amber pendant in cross shape (Fishamble Street)

This pendant was made for me by my friend Peter Merrett, based on an example found on Fishamble Street (E190:6248.) It was dated to the mid to late 10th century.

My version is in a lighter amber than the original, which was more orange. Lots of amber fragments were found in the Wood Quay area and particularly in Fishamble Street. Wallace (2016, p.291) explains how at least one house specifically (FS 20 at building level 5 in yard 2) showed evidence that it was the main centre of amber production in late 10th century Dyflin. 257 objects were found in and around the site, while 1,240 worked amber pieces in various stages of completion were also discovered there.

Amber was found in fifty-three of the buildings on Fishamble Street, with 41% of them being recovered from FS 20 and its yard. The Dublin amber finds were made up of beads, pendants, rings and of course the waste and unworked amber nuggets. While some of the amber items for sale in Dublin may have been for a foreign market, it seems that the cruciform pendants had a local flavour- cross pendants in amber haven’t been found in England and the English jet crosses aren’t especially similar in style in my opinion.

Since amber would have been a commonly traded good in the Wood Quay neighbourhood, I envision my Dublin woman as having a piece or two. Perhaps like me, she bought her cross pendant from her craftsman friend up the road or indeed, perhaps she was the craftsperson herself.

Bone bird-headed pin (Winetavern Street/Christchurch Place)

This pin is based on a bone pin (E122:61) found on either Winetavern Street (Wallace, 2016. p.303) or Christchurch Place (National Museum of Ireland, 1973)- different publications give different find sites. It has a carved terminal in the shape of a bird and was dated quite vaguely to the 10-11th century.

A multitude of bone pins were found in Viking Age Dublin. Like the York examples, they range from plain all the way to ornate- some of the more decorative examples include cruciform tops, ram’s horn and animal-headed. We can’t tell for certain if they were used for fastening clothing, as hair pins or indeed for some other purpose.

Do you think it looks more like a swan or a goose, a duck, a pelican? I can’t decide but I like it a lot.

Copper alloy toiletry set (Fishamble Street)

Toiletry sets like this one (E190:0000) are a relatively common find across the Viking world- other examples can be found from York, Hedeby, Birka, Gotland and many other sites. Mine is one of two found on Fishamble Street and is dated to the 10th century. It is made of copper alloy and consists of a little tube, hanging from a ring by a chain, along with several other tools- a pair of tweezers, a nail/tooth pick and one other unknown item which was broken.

The tube would have been used as a needlecase, either with a roll of fibre shoved inside with the needles or indeed with something blocking each end to make a sealed tube. Other examples from the Viking world indicate that sealed needle cases were common, though neither needle case found at Wood Quay had a stopper or a lid. I put a little linen cloth inside mine, more for appearances than anything else. The needles that your Hiberno Scandinavian lady would carry with her could be made from iron, copper alloy or bone- needles are a common find at Viking Age sites.

Textiles

I didn’t plan the textiles for this outfit specifically for a Dublin impression- so they aren’t perfect. I opted for a mustard yellow wool dress and a diamond twill shawl in a khaki green-mustard. Both colours can be achieved on wool using natural dyes used in period, namely dyer’s greenweed and weld.

In the absence of any Viking Age tunic finds from Ireland, the pattern for my dress was based on the 11th century Skjoldehamn find from Andøya, Norway. It has four gores from the waist, two at the sides, one at the front and one at the back. I feel like this gives a more swooshy skirted look that I really like and that fits with what few contemporary images of women from Ireland and Britain we have. My shawl is rectangular with tassels at each end.

The dress is made from a simple 2/2 twill, which is found commonly at many Viking Age sites. Under normal circumstances, I would also wear a tabby woven linen underdress- but I couldn’t fit one in my luggage! Next time, I’ll take the longship instead of flying Ryanair.

Pennanular brooch

For some stupid reason, I didn’t take any photos of the brooches in the museum! They’re in the background of a few other glamour shots of the toiletry sets, mocking me, but not sharp enough to show. Sorry!

Preferably, I would have a suitable little disc brooch to close my neckline for a Dublin impression. 30 such brooches have been found in 10-11th century contexts there and Wallace (2016, p.368) describes how they were likely imports from England or Germany, where they were very fashionable at the time. It’s also striking to note how similar many examples are to York and London finds. That being said, I didn’t want to use York brooches for a Dublin outfit! I’m searching for a good replica as we speak.

One example of a pennanular brooch from Fishamble Street is E190:6455. It’s made of copper alloy and dates to the 10th century. Wallace (p.280) relates this to another brooch from Ballinderry crannog among others, labeling the penannular style as an indigenously Irish one. He explains that this could indicate that Hiberno-Scandinavian townspeople had a taste for Irish jewellery or simply that an Irish person came into the town wearing their own native fashion.

Bonus photo dump: street signs and Wood Quay pavement plaques

I’m just a massive nerd and I love seeing the street names I recognise from the archaeological reports.

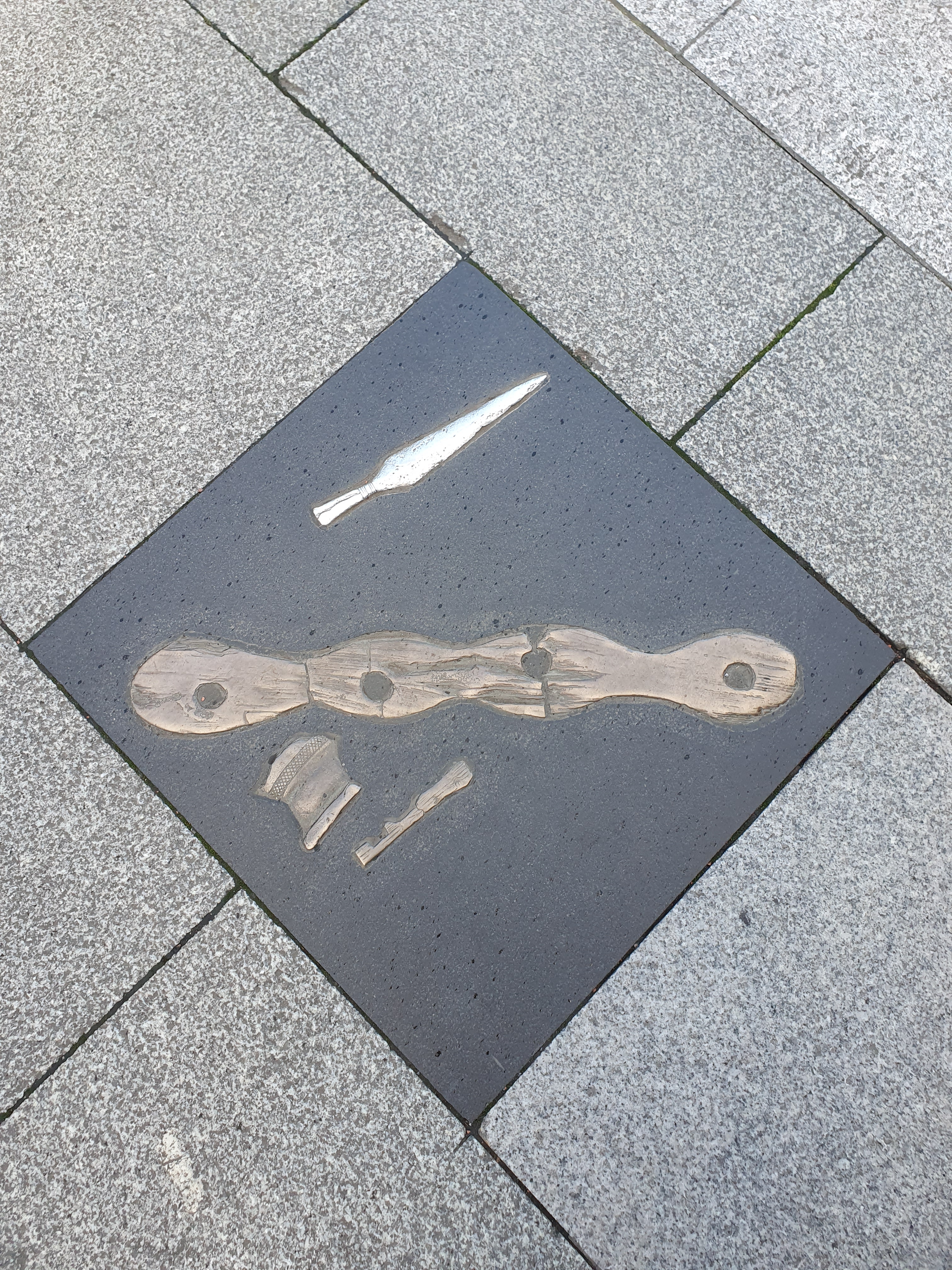

There are a series of bronze plaques in the pavements round Wood Quay, made by sculptor Rachel Joynt. An attempt to remind those walking the street of the history beneath their feet, they feature a great selection of the finds from the area- including a familiar bird pin!

Another cool thing in Wood Quay is the outline of a few Viking homes on Winetavern Street. I took my photos stood in the porch of one such house, in the shadow of the cathedral and flanked by the imposing Dublin City Council offices. It was really cold that day, but it was powerful to stand in a little open space and to envision what came before and the quiet street that sits here now.

This was a spur of the moment thing and not as polished as I would normally like. I’m planning on finishing this set of clothing and have another one in the works- but I still had so much fun.

References

National Museum of Ireland (1973) Viking And Medieval Dublin. Catalogue of Exhibition . Dublin: An Roinn Oideachais. p51.

Wallace, P. F. (2016) Viking Dublin The Wood Quay Excavations. Sallins: Irish Academic Press. p1-558.

Wincott Heckett, E. (2003) Viking Age Headcoverings from Dublin. Dublin: Royal Irish Academy.