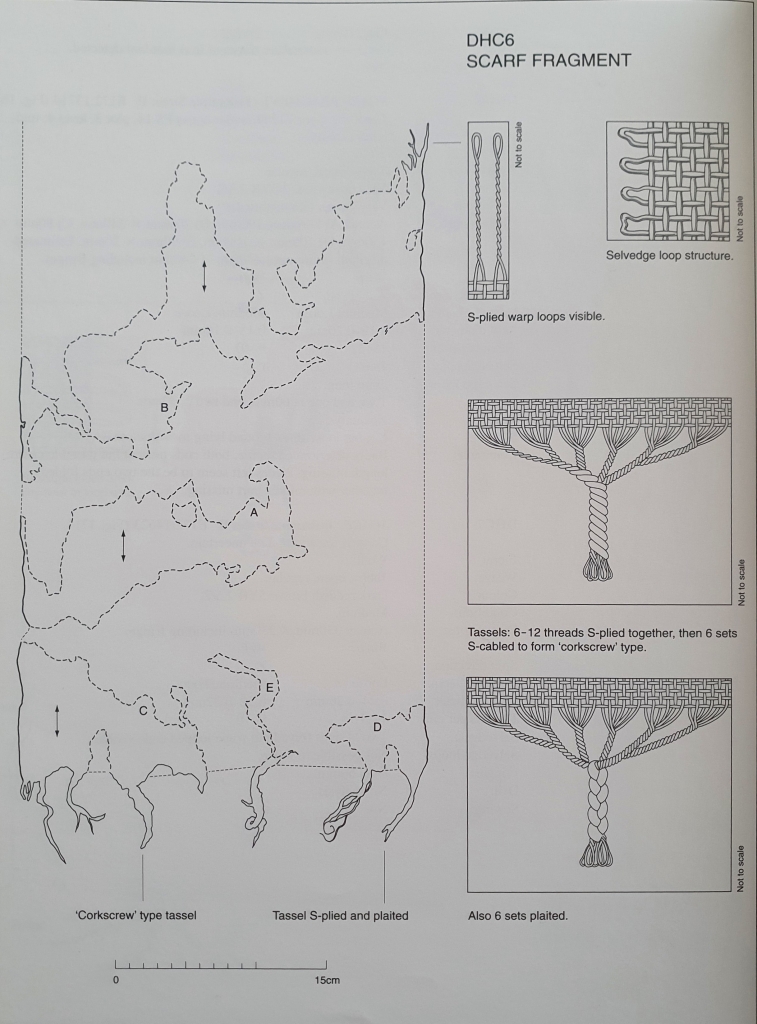

This wool scarf is based on fragment DHC6, found at Fishamble Street II and dated to a mid-10thC context, find number E172:13714 (Wincott-Heckett, 2003.)

The fragment was estimated to have been 450mm by 240mm originally, including fringes at each end. I made mine to the same dimensions. Like most of the Dublin headcoverings, DHC6 was woven to size, which mine was not (meaning I had to do a small rolled hem each side.)

DHC6 was not analysed for dye, but it was described as being “very dusky red” in colour upon conservation. Many of the fragments were described thus, even those in which no evidence for dye could be found. The scarf I made was a natural light grey colour, which I overdyed with a weak fresh woad dye I happened to have on the go. Indigotin was possibly detected on another Dublin scarf, the silk fragment DHC12.

This scarf is the first I’ve made of this type and tasselled by hand. It felt like the fringe took a thousand years, it was not my favourite task. This is despite the fact that the tassels on many of the Dublin scarves are longer and more complex than the ones I did here. I can only assume that the folks making these scarves historically were skilled and very used to tasselling things, meaning they didn’t feel like they were losing their religion like I did.

This fragment is assumed to be a headcovering and since it (and the others recovered from Wood Quay) are not grave finds, we have to rely on assumptions. I tried it on several different ways to see how it looked and well:

It is safe to say that it is a bit goofy-looking. This has never stopped me however, so undeterred, I just accessorised more:

The wool fillet didn’t do much, except for cover up some of my formidable forehead. I tried it over the top of the scarf, which would at least add stability and make me look less like the Flying Nun.

This way of wearing it did seem to be more suitable for day-to-day use and resembled the silhouette of Dublin or York caps more closely (not that this is necessarily the purpose.) It is suggested by Wincott Heckett (2003) that these scarves could have been worn as headbands or around the shoulders, which wouldn’t be possible with this scarf as it is just too small. I will test those ideas when I make some other scarves based on larger fragments, some dyed and some undyed.

References

Wincott Heckett, E. (2003) Viking Age Headcoverings from Dublin. Dublin: Royal Irish Academy.