Location: Wood Quay, Dyflin (Dublin), Ireland.

Date: Mid 10th century and mid 11th century.

Culture: Early Hiberno-Scandinavian.

Estimated Social Status: Affluent urban freewoman.

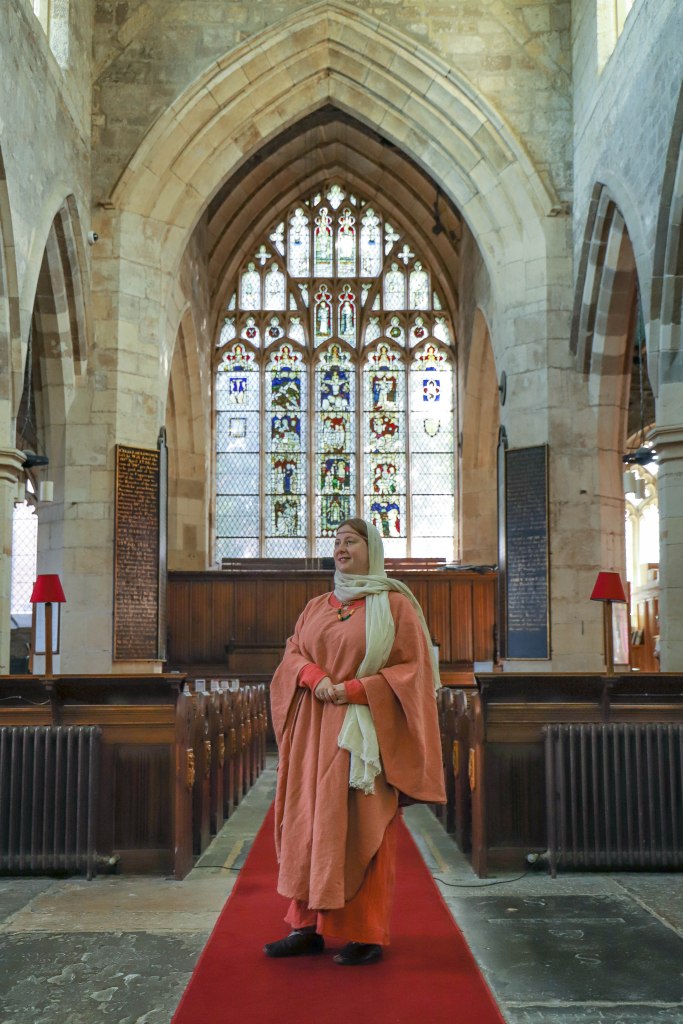

The following photos show two sets of speculative clothing based on archaeological finds from Viking Dublin, set approximately a century apart. My goal is to combine these items according to their proper dating and present them in context, to provide a more whole view of how a citizen of Dylfin could have looked. I also aim to demonstrate how fashion changed over that century, even if the changes might seem modest or slow when compared to our modern world.

It is unfortunate that there are almost no contemporary detailed images from Viking Dublin that show the people who lived there. As a result, I must rely primarily on metal, glass and bone items that have survived intact, with clothing being based upon Hiberno-Scandinavian textile remains from the town, Scandinavian finds and contemporary illuminations from Britain and Scandinavia. As a result, my interpretation is just that- an interpretation. You might examine the evidence available to us and come to a different conclusion of how it should be combined and therefore how people may have looked. That’s quite alright too!

As usual, unless mentioned, all photos are my own. Any photos taken from archaeological publications are referenced and used here for educational purposes. Most of the kit photos are taken on Winetavern Street, Fishamble Street or in the grounds of St Audoen’s Church on High Street, all areas of Dublin inhabited in the Hiberno-Scandinavian period.

Mid 10th century outfit

Dublin cap (DHC33.) Early-mid 10th century, Fishamble Street.

If this cap looks familiar to you, it is because I have already written about this last month in its own article! In dimensions, material and fabric weave, this wool cap is based on cap DHC33, as described in Wincott Heckett (2003.) It is woven in a plain/tabby weave and dyed by me with madder, though the original cap was not subjected to dye analysis. The braid on the front edge is made from naturally pigmented brown yarn and whipstitched in place.

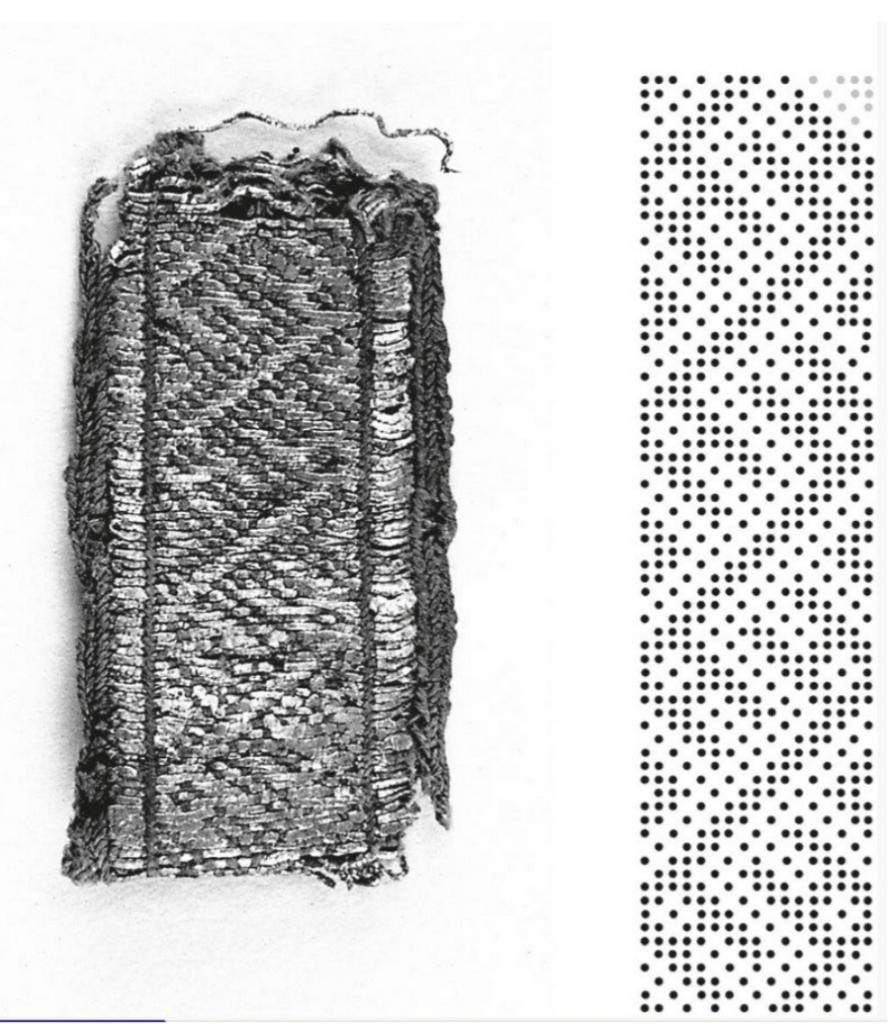

Gold and silk brocaded headband (E190:1194) 10th century, Fishamble Street.

This is a famous and much-replicated find among re-enactors. The so-called “Dublin dragons” motif is described by Pritchard (2021) as “gold-brocaded tablet-woven band, width 9 mm made with 31 tablets from Fishamble Street, Dublin.” Most bands seen in re-enactment with this pattern will be much wider than 9mm (no judgement- I love this pattern and have several very pretty wool items woven in this pattern!) but for this, I wanted something closer to the original. The extremely talented Alicja of Kram Ammy on Etsy wove this for me and despite using the finest silk she had, she still wasn’t able to weave it any narrower than 10mm without the pattern becoming warped. It dates to the latter half of the 10th century, though several other brocaded silk bands were found in Wood Quay in the 10th and late 11th century layers.

As all of the tablet woven remains at Dublin were fragmentary and not in a grave context, we are left to imagine of what they were originally part. Pritchard (2021) has suggested that they were part of narrow fillets (or at least in conjunction with some headcovering) following the contemporary evidence from Scandinavia- she says that in terms of technique, the Dublin brocaded bands are closest to finds from Denmark. No dye analysis was conducted on the silk part of E190:1194, but madder has been found on other silk and wool textiles in Dublin so I opted for a bright madder red. I’ve seen some truly stunning replicas done in ivory silk and gold (which could very well be what it looked like if the silk was undyed), like this example by Kristine Vike.

Lozenge brooch in lead alloy (E81:4681.) 10th century, Winetavern Street.

The brooch at my neckline is a pewter lozenge brooch, a style from England originally that made its way to Viking Dublin in the 10th century alongside the more common disc brooches. (Wallace, 2016.) Lead alloy jewellery items like these brooches have been found in large numbers at several English sites, most notably York and Cheapside in London, where they were most likely being produced. (You can see the whole Cheapside Hoard on the Museum of London collections website.) It is of course possible that local copies of these foreign pieces were being produced in Viking Dublin, but we cannot know for sure if this example is imported or a homegrown copy.

Such items would have been affordable and easy to produce, but might have cost a little more than some of the simpler styles of fastenings made from wood or bone. (Mainman & Rogers, 2000.) My version is not a replica of E81:4681, as I couldn’t find anybody making them. It is however a copy of an extremely similar brooch found in Lincolnshire, made by Blueaxe Reproductions.

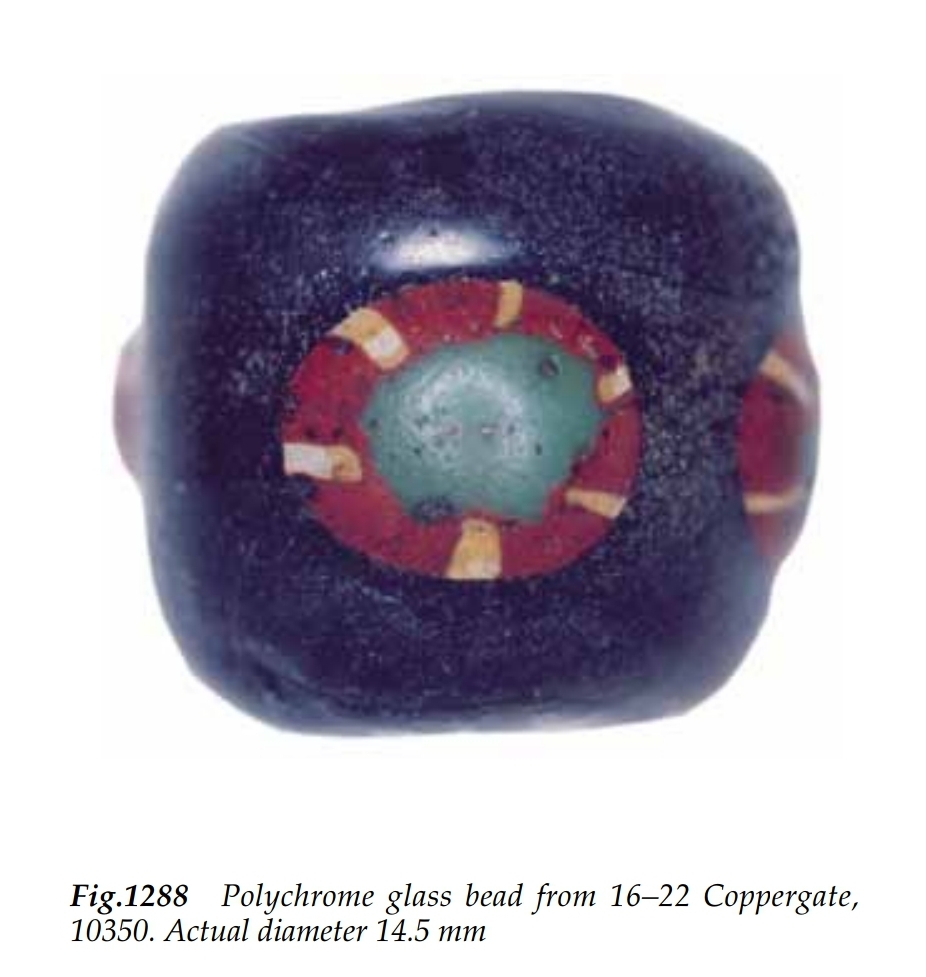

Bead necklace (E81:4869 & E81:4870.) 10th century, Winetavern Street.

The Catalogue of Exhibition (1973) for the National Museum of Ireland describes E81:4870 as follows: “Thirteen green glass beads, two amber beads and four fragments of green glass beads (not exhibited.) The glass beads are globular and coiled and measure from 3mm. to 7mm. long. The amber beads, light in colour, are 6mm. in diameter. 10th century. Winetavern Street.” with E81:4869 being described as “Similar in every way to those described above.” They were found scattered together in the same area in the street, so were catalogued and displayed together.

I put together my necklaces using some vintage green glass beads and some faux-amber glass beads from Tillerman Beads. My beads are ever so slightly larger than the originals and they are far more even- the original green glass beads were quite crudely made with lots of lumps and bumps. They are however close in colour and size, with the threading order being left up to interpretation. It is unknown what the originals were threaded with due to deterioration of the threading medium, but I chose to use undyed linen thread as it would have been readily available at the time.

Wool dress in 2/1 diamond twill, mimicking lichen purple (and woad?) dye. 10th century, inspired by several Dublin textile fragments.

My 10th century dress is made of a lightweight and fine 2/1 diamond twill wool, which was bought secondhand from a friend. It was not dyed naturally, but with modern chemical dyes in the pursuit of quite a different shade than it ended up. I use it here in order to mimic a shade of lichen purple, a dyestuff that was found on numerous textiles in Viking Dublin (Walton, 1988.) An exhaustive catalogue of all the textiles found in Dublin (of the kind we have from York!) is sadly not available to my knowledge, so basing my textiles on specific individual finds has been challenging. Pritchard (2020) does however mention a mid-10th century fragment of 2/2 chevron twill from the Fishamble Street site that tested positive for lichen purple and describes it as the “finest of the warp-chevron twills” from that deposit. The finest examples of twill weave wools from Dublin are equivalent in quality to those found in high status contexts at Cnip, York, London and Birka. This indicates that there were Hiberno-Scandinavian folks living within Dyflin that had both the money and connections to own some very nice cloth, potentially imported from abroad. (Pritchard, 2014.)

When it comes to lichen purple itself, I cannot be certain that this shade is perfect as it was not dyed naturally. There are a great many species of lichen that produce orchil dye and many of them produce more of a magenta or hot pink than a modern purple! Lichen are also slow-growing and many species are protected, so collecting them for the purpose of anything other than mini-dyebaths is generally discouraged. If you are not convinced by this colour representing lichen purple alone, there is a contemporary find of fine diamond twill from London dyed with lichen purple and woad, both dyestuffs being commonly found (albeit not together) among the Dublin textiles (Pritchard, 2020.)

Another cool thing about this fabric that I wasn’t sure where else to mention: it has been suggested that fine diamond twills like these were being polished by Viking Age Dubliners in order to bring out the natural check pattern that is produced when weaving them. The broken remains of what is thought by archaeologists to be glass smoothing stones (found all over the Viking world, including in York) were recovered during the Dublin excavations. When rubbed with a smooth surface like these glass proto-irons, it can cause the surface of wool cloth to become shiny and smooth, bringing out the details of the weave (Pritchard, 2014, 2020.) I think that’s pretty cool, but it has not been proven just yet!

In terms of pattern, I kept it very simple as I generally do. I made a slim-fitting skirted dress with side gores from the waist, underarm gores for movement and a round keyhole neckline. The tunics from Skjoldehamn, Moselund and Kragelund (dated to late 10th-early 11th century) all feature similar constructions with mostly rectangular bodies and triangular gores to add width and shape. Contemporary English, Scandinavian and Continental sources show ankle-length dresses fitting this silhouette on all female figures. You might also notice that my side gores have been pieced using offcuts- this is not based on a specific Dublin find, but for economy. Piecing is evidenced in several extant Viking Age garments and it demonstrates that historical people didn’t necessarily share our need for symmetry. My dress is handsewn using fine linen thread, waxed in beeswax.

Underneath, I’m wearing a bleached linen underdress of much the same construction and pattern.

Needlebound textile, based on fragment (E190:7430.) 10th century, Fishamble Street.

I am currently working on a pair of needlebound socks using the Dublin stitch, which was used in a tiny fragment found in Fishamble Street. The original fragment is too small to determine what item it belonged to, so I am taking inspiration from the York sock (the stitch type of which seems similar in structure to Dublin stitch!) E190:7430 is described in Pritchard (1992) as being made from two-ply (Z/S-ply) wool yarn dyed with lichen purple.

Since lichen purple is hard to come by and takes a long time to produce, I used a naturally dyed purplish madder yarn that I obtained several years ago at Wolin. My goal is eventually to have some real lichen dye to dye a fleece with and spin it into some yarn suitable for a better quality E190:7430 replica.

Cloak in 2/2 diagonal twill, mimicking woad dye. 10-11thC, based on several textiles from Fishamble Street and other Dublin sites.

My cloak is a very simple square item measuring approximately 150x150cm, made by me from a heavy wool twill from Old Craft. Two of the edges are selvedge and the other two I unravelled for a fringe on each edge. I’m gradually working my way through tasselling it, though the current fringe seems to be holding up admirably in the meantime. It is not naturally dyed, but is similar in shade to a deep woad dye. Heavier twills using thicker and coarser yarns were found among the Fishamble Street textile assembly (Pritchard, 2014.) It is thought that some of these heavier twills may have made up outer garments like cloaks, though no whole cloak has been found there. A comprehensive discussion of the evidence for women’s cloaks in the Viking Age by Hilde Thunem can be found here.

Some of these heavier twills show evidence of pile having been inserted into the weave, which would result in a shaggy and hard-wearing textile somewhat like a woollen faux fur (Pritchard, 1992.) 10-11th century finds of this type of textile from all across the Viking world supports the idea that shaggy cloaks were quite fashionable and it has been suggested that Ireland could have been one of the areas producing them. I’m already working on a pile woven cloak based on York fragments, but perhaps when I have a spare few months (so never), I could warp up my loom and weave myself a shaggy Dublin mantle. Watch this space!

Regarding the brooch, it is an Asgard replica of a 10th century York find, 10601. (Mainman & Rogers, 2000.) Similar to my lozenge brooch at the neckline, I faced the problem of no jewellers selling good quality replicas of the Dublin finds. If I am wrong, please tell me- this is a case where I would love to be wrong (though my wallet may not.) In the discussion of my lozenge brooch, I mentioned that mass-produced lead-alloy brooches were being imported into Dublin from England, many of them being disc brooches. Over 30 disc brooches were found in the Dublin excavations (Wallace, 2016) and it’s fascinating to see how similar some of them are to finds from London and York.

So, I decided to choose a York brooch that was as similar to one of the Dublin examples as I could and I settled on York’s item 10601 as a replacement for Dublin’s E122:1 (found in Christchurch Place.) They are both cast lead-alloy disc brooches, decorated with a florid scrollwork design in the centre and surrounded by rings of “beaded” borders. This is a very English design and judging by their geographical spread, it would seem that mass-produced brooches like this were popular in Early Medieval trade centres like Dublin. While they were especially popular in the 10th century and that is when they first appear in Dublin, I could very well have worn this disc brooch for my 11th century impression too, as their popularity did continue well past 1000AD.

Mid 11th century outfit

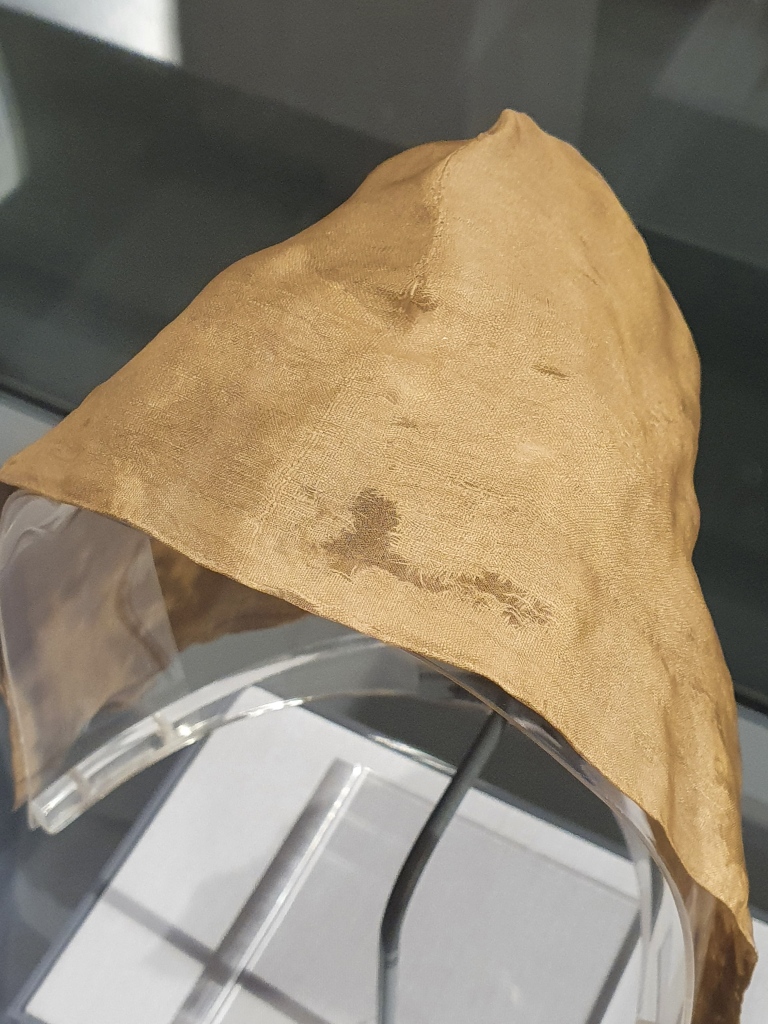

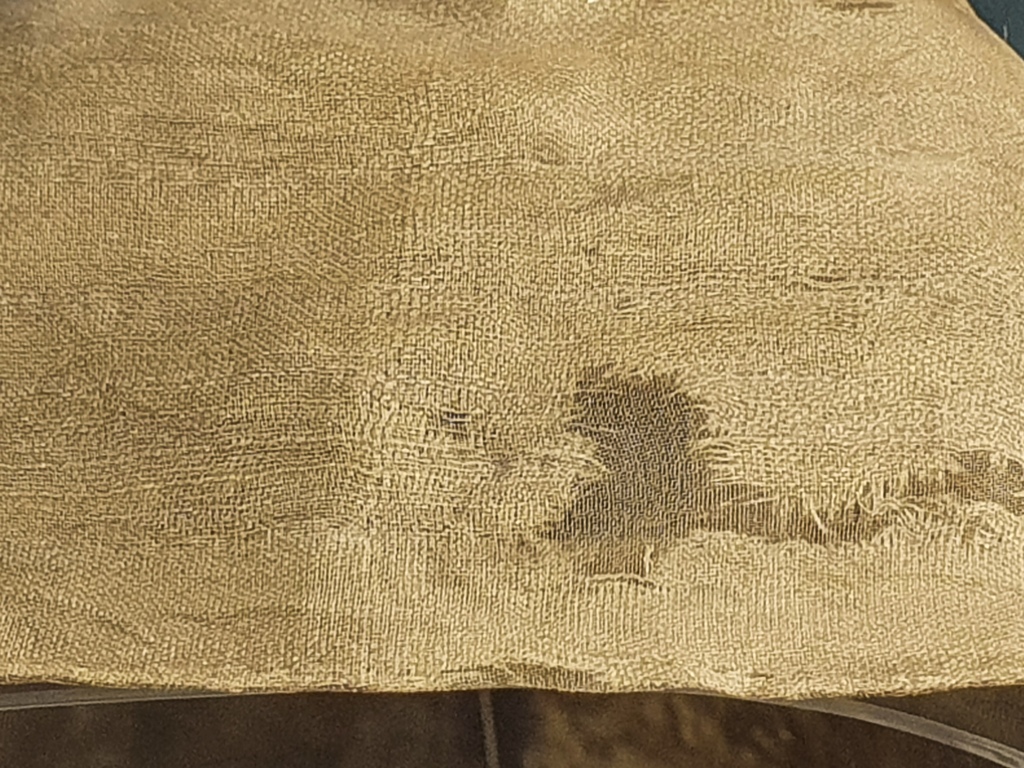

Silk veil (DHC17 or E172:9115) Early 11th century, Fishamble Street.

DHC17 is described as follows: “Veil-type cloth. Fishamble Street II, E172:9115. (…) Fibre: Silk. Weave: Tabby, open. Colour: Reddish brown (…) retains remains of red colour. (…) Dye: Analysis undertaken; lichen purple detected.” (Wincott Heckett, 2003.)

My replica of this item was made by Blueaxe Reproductions, using silk hand-dyed by the Mulberry Dyer. It is made to the same dimensions as the original and it is interesting to note that while this is the largest headcovering found in Viking Dublin, it doesn’t come close to the size of many veils or wimples seen in contemporary English art.

It is my personal belief that while DHC17 was undoubtedly a luxury item made from imported material, it could very well represent wealthy urban fashion as opposed to that being worn by the very highest echelons of society at the time. This could explain the restrained size of the item when compared to the idealised depictions in artwork, as it is not only more economical but prudent to wear a slightly less huge and voluminous piece of cloth in the muddy lanes of Dyflin, even if you are wealthy. This theory also applies to the size of silk caps found in Dublin and other Viking trade centres, which in reconstruction very rarely cover the whole head of an adult (I don’t buy the idea that they were all children’s garments.)

The size of DHC17 also contributed to my decision to wear my braids down- unless worn in conjunction with and weighed down by a heavy cloak, it’s not really possible to get DHC17 to cover your whole head and neck. It’s possible that commoners may have been less strict about covering their entire head and hairline in the way we see in artwork, so I tried that out here. We really don’t have much to go on, other than the remains of headcoverings (which are skimpy) and the drawings of veiled women (which are decidedly not skimpy.) A tiny 11-12th century figurine in the National Museum of Ireland (item 2002:85) is probably Irish rather than Hiberno-Scandinavian, but she also bucks the veiled trend with her braids and I am enchanted by her:

She is made from copper-alloy and came from an unknown locality in Ireland, which really sucks because she is adorable and a rare detailed female depiction from this period. If you really disagree with this styling of my veil for an 11th century impression, rest assured- I restyled it later when putting on my cloak and it resembles a more traditional 11th century silhouette.

Due to heavy winds while we were taking pictures of the rest of my outfit, I had to secure my veil with my brocaded headband in order to avoid losing it! While the Dublin dragons fragment dates to the 10th century rather than the 11th, these brocaded silk fillets were very much still in fashion by the time DHC17 was being worn. Remains of another gold brocaded band were found in nearby Christchurch Place, dating to the late 11th century. (Pritchard, 2021.)

Wool dress in 2/2 diamond twill, dyed with indigotin. 10-11thC, inspired by several Dublin textile fragments.

My dress is made from a 2/2 diamond twill wool, dyed using indigo- Viking Age Dubliners would have used woad, but the colour compound in indigo and woad (indigotin) is the exact same. Preferably I should have used a 2/1 diamond twill for this project: Pritchard (2020) notes that while 2/2 diamond twills do appear in 11th century levels at Fishamble Street, they are rare. Interestingly, plain 2/2 weaves made up the largest group of textiles at this site. Next time, I would replace this either with a 2/1 diamond twill or a plainer diagonal twill, which would be more inkeeping with evidence for Fishamble Street at this time. Underneath, I am wearing the same bleached linen underdress as I did for my 10th century set.

In terms of pattern, my blue dress is very similar to my purple one. To what extent we can really recreate a 10th century dress versus an 11th century one is limited, as we have no finds of dresses or even tunics from Ireland (or even from Britain!) for this era. My 11th century dress does have gores at the sides to add width at the skirt, but by the 11th century, women’s fashion tends to favour a long and relatively slim silhouette with skirts not being drawn as voluminous. This suited me well, as my fabric was composed of an offcut and I did not have the cloth to add too many gores.

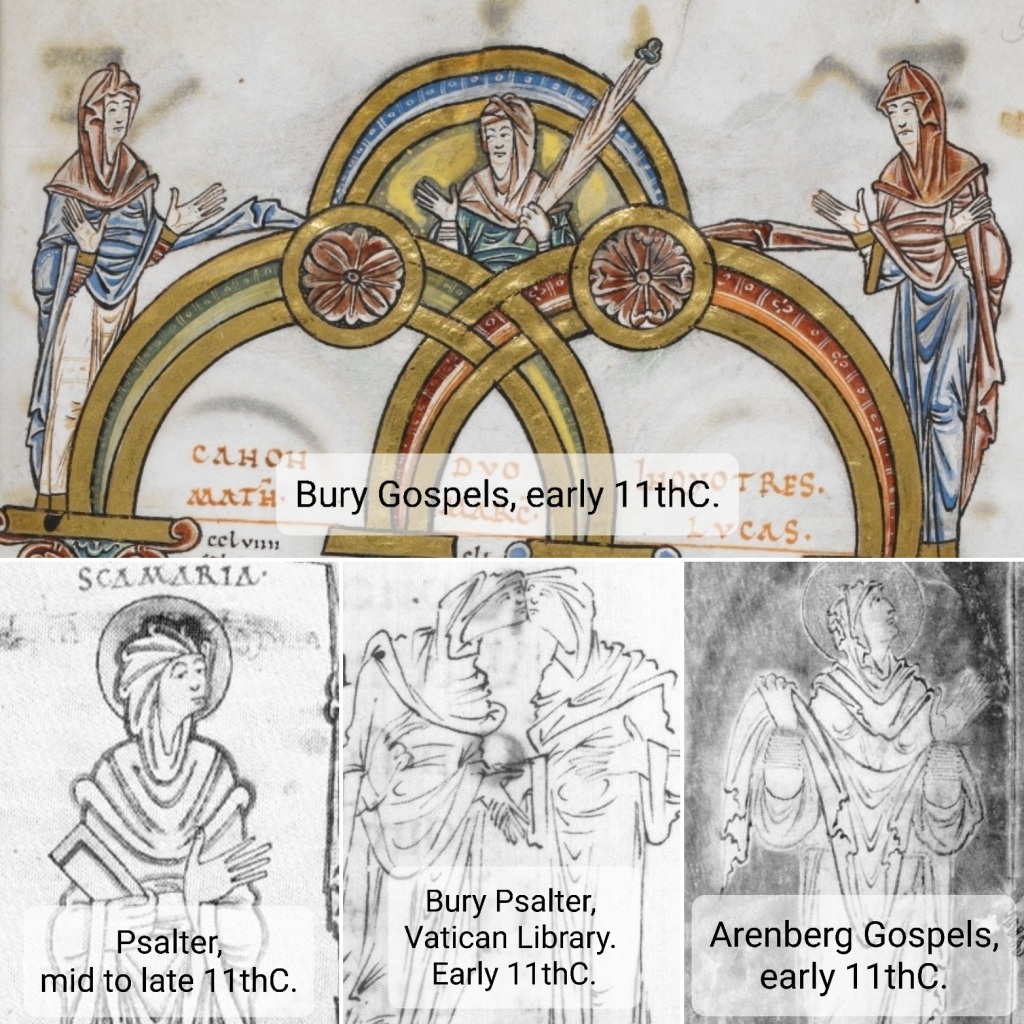

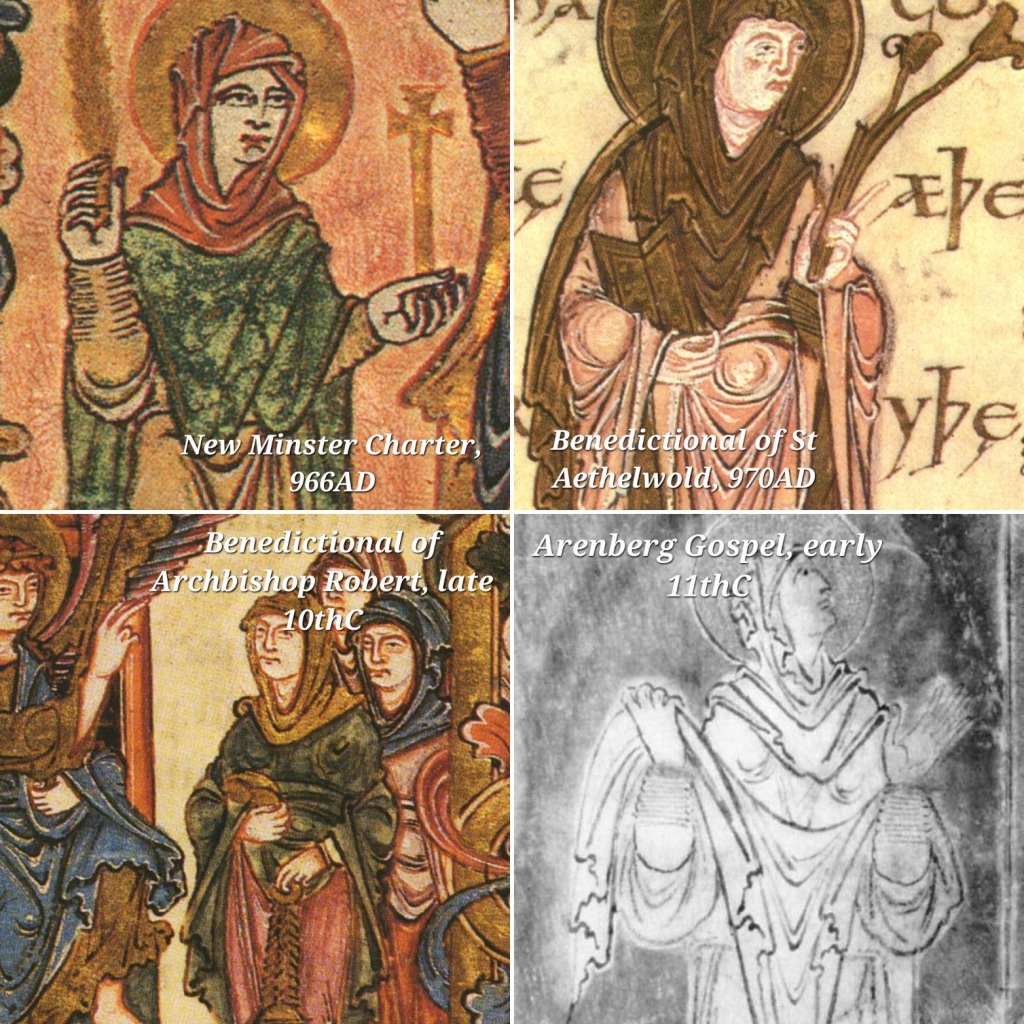

For my sleeves however, I did use a slightly looser cut, a trend which can be seen in English and Continental manuscripts from the 10th century onwards and only increases as the 11th century goes on. These sleeves would eventually become extremely wide (examples can be seen on queenly figures) and must be related to the Norman bliaut that would become in vogue in Britain after the Norman Conquest. Examine these examples of English illuminated manuscripts and artwork from the mid 10th to late 11th century and keep in mind that by the 11th century, a significant portion of the country’s ruling class was Anglo-Scandinavian:

As my Dublin 11th century lady is an urban commoner, I doubt that she would be sporting the floor-length sleeves of the royals. It would be incredibly impractical and potentially outside her price range, especially if she was using imported cloth. It is however my belief that she would be aware of the trends from abroad, as she lived in a bustling trade centre that we know was receiving regular imports from Britain and the Continent. While it’s unlikely that she would have access to the illuminated manuscripts featuring the elite that we use as our sources, we can observe a general trend of sleeve growth when comparing images of women throughout the Early Medieval period in Northern Europe. I see no reason why this trend could not have been reflective of actual clothing being worn contemporarily. I therefore feel comfortable in my mercantile lady indulging in a slightly baggier sleeve on her overdress than her grandmother might have.

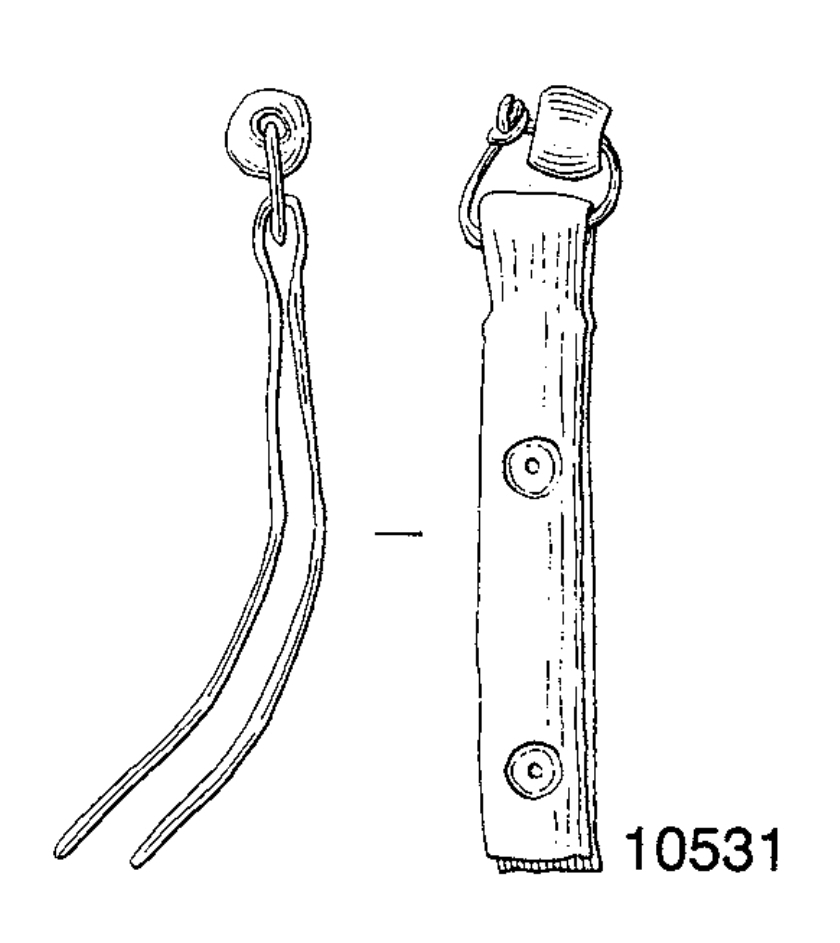

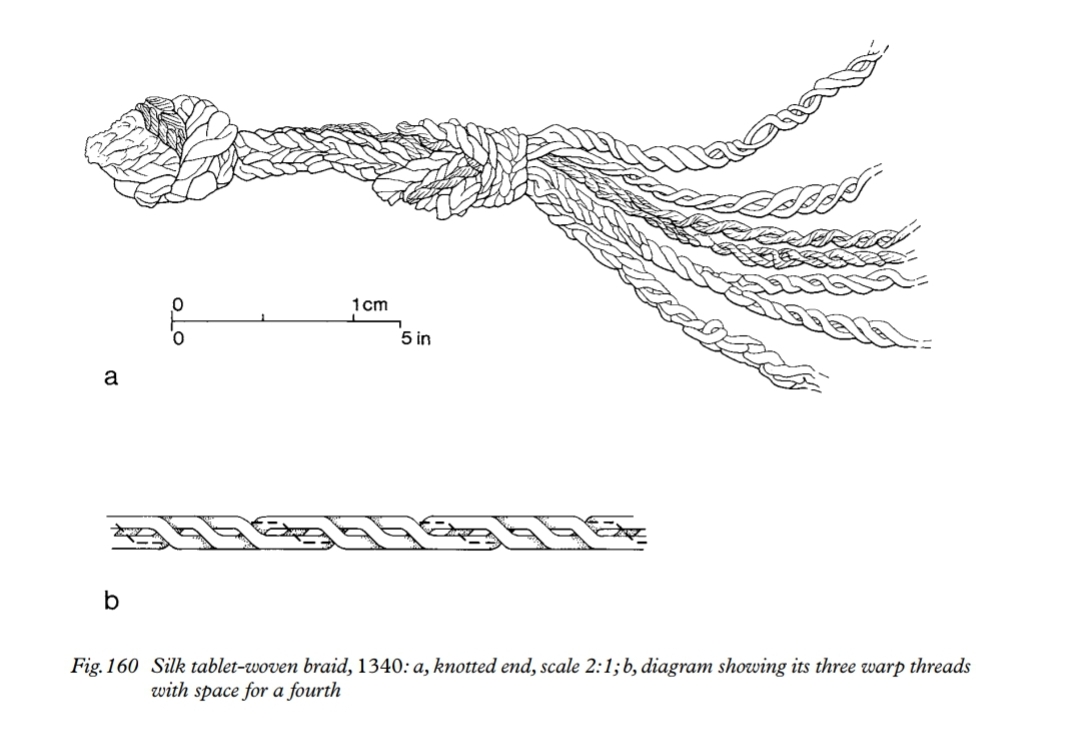

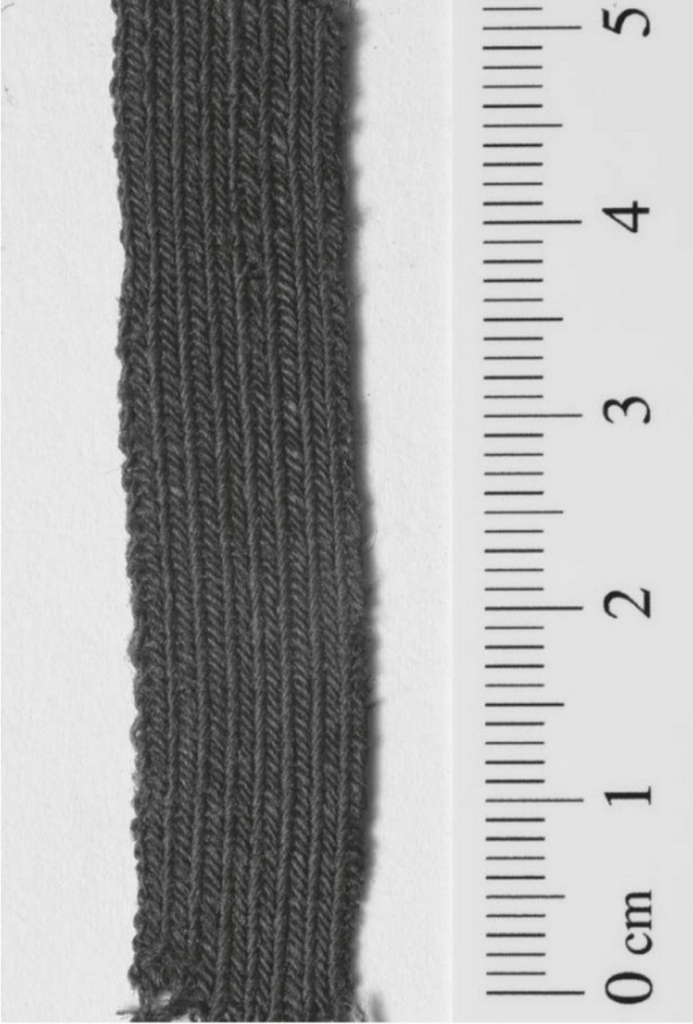

Tablet woven belt (E172:11815.) Late 10th- early 11th century, Fishamble Street.

This belt is based on tablet woven fragment of woollen braid, found in Fishamble Street and dating to the late 10th- early 11th century. The original item E172:11815 was woven on 16 four-hole tablets using a wool yarn of semi-fine fleece type (Pritchard, 2021.)

As I could find no details of dye analysis and images of the band show no discernable colour, I wove my first version in a naturally pigmented dark wool. Eventually my goal is to replace this with another replica made with a smoother and finer yarn, dyed with one of the natural dyes found on other Viking Dublin textiles. A smoother yarn would also improve the texture of the band, as the original still shows its pattern well and it is less defined on my version.

To what extent belts were worn by women in Viking Age Dublin is not known. As I wished to include my tooled leather knife sheath in this impression, I chose to include a belt so the sheath could be suspended from it. The original purpose of E172:11815 is also unknown as it survived only as a fragment, but its narrow width of 12mm and plain weave makes it quite suitable as a belt.

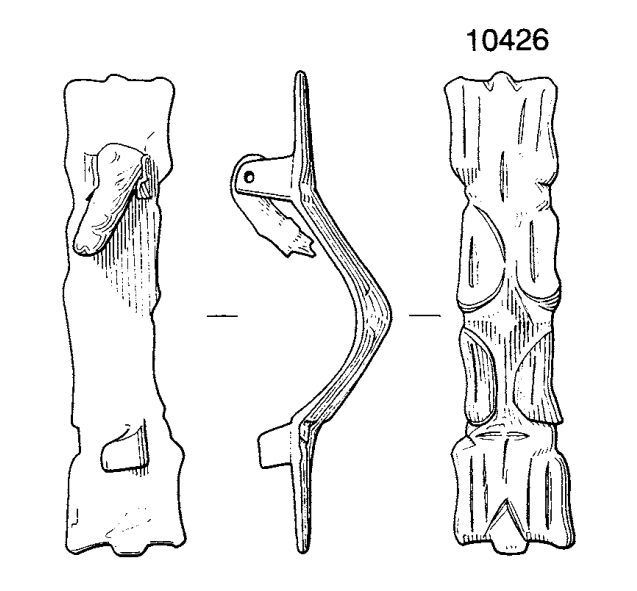

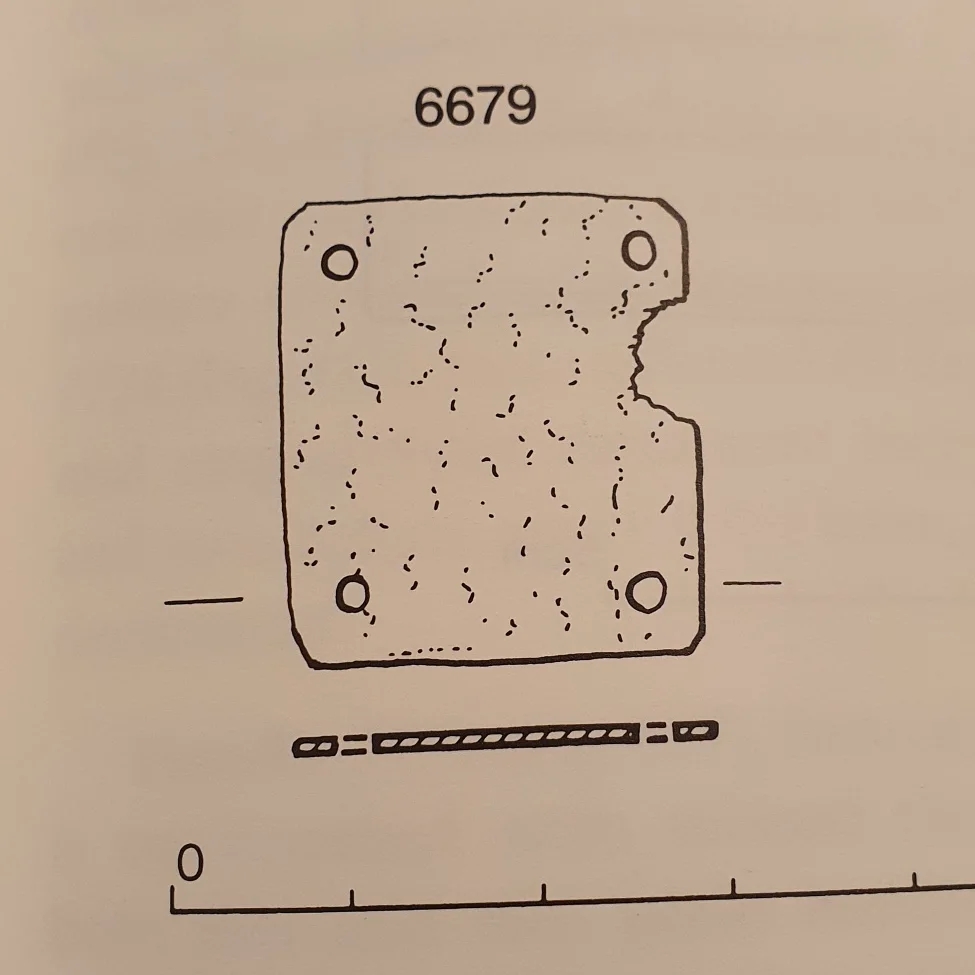

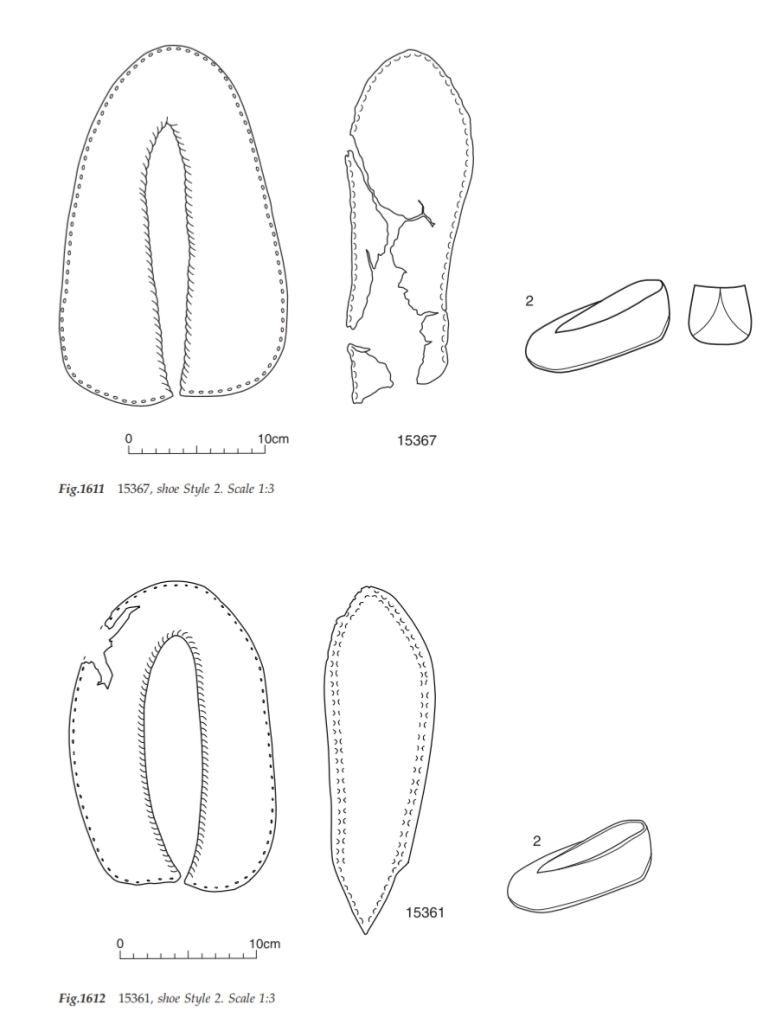

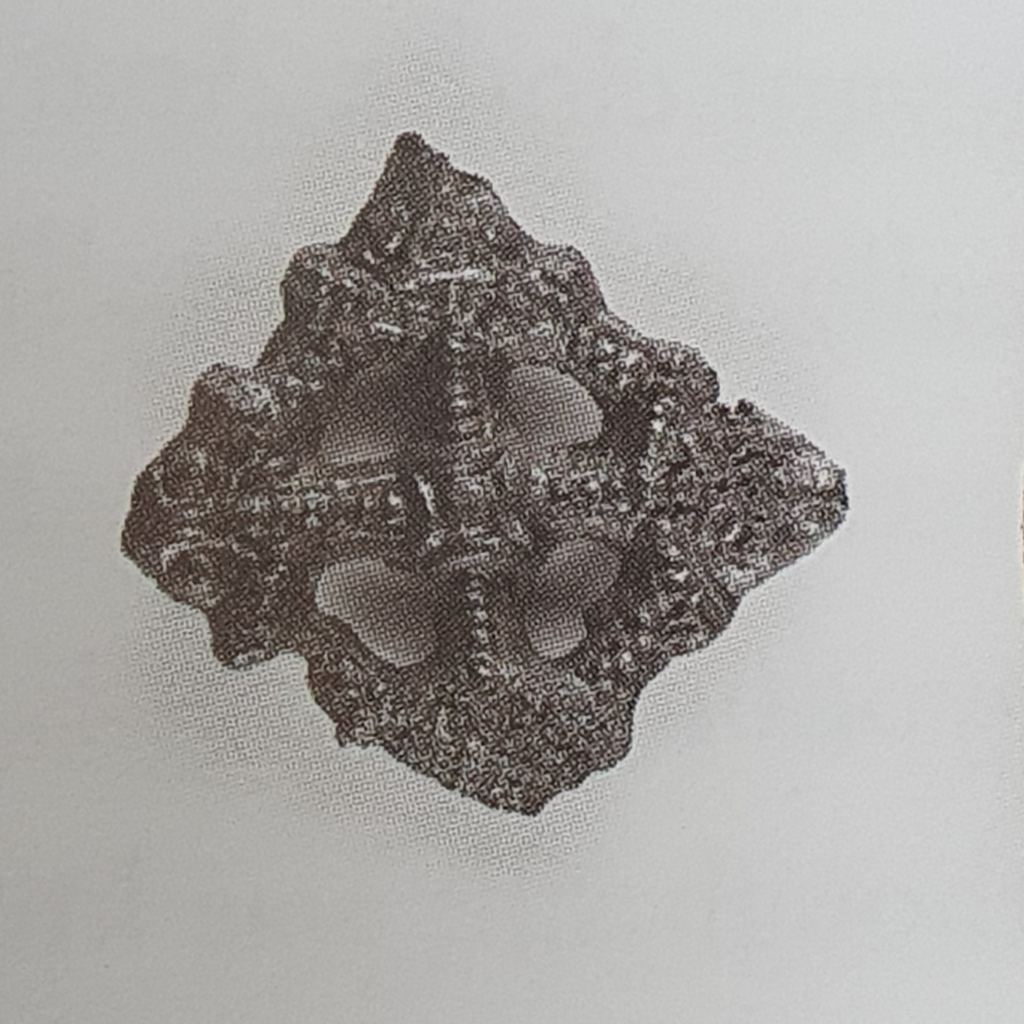

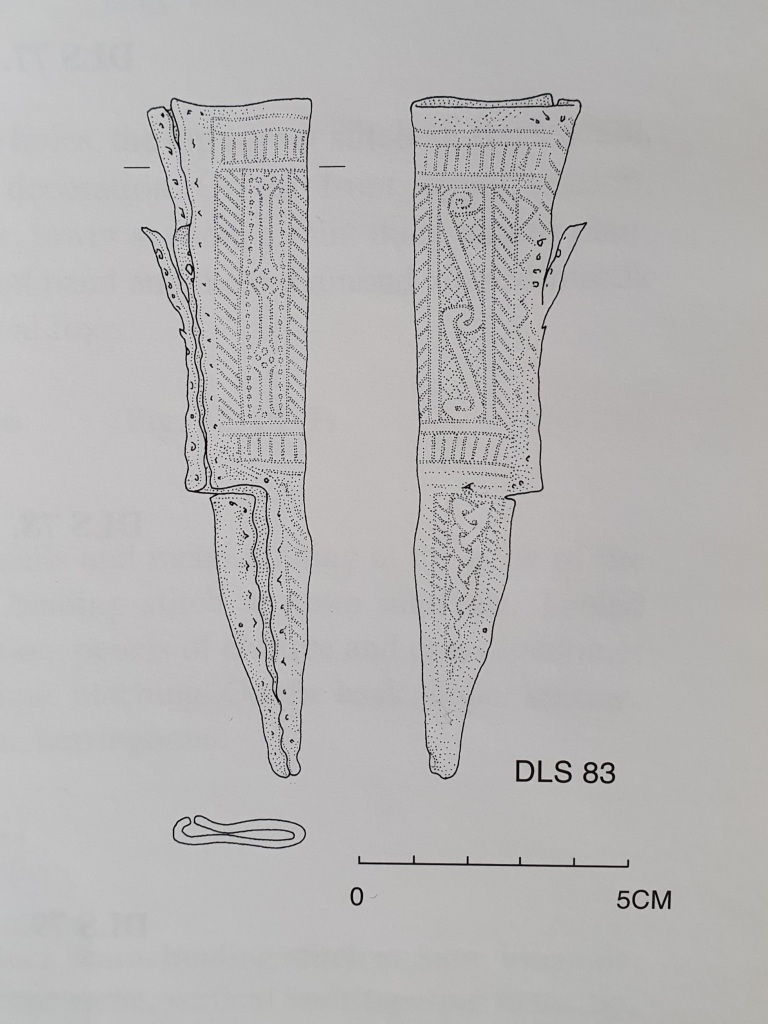

Tooled leather sheath (DLS 83 or E122:13138.) c. 1050-1070, Christchurch Place.

The leather sheath DLS 83 or E122:13138 is described in Cameron (2007) as follows: “Sheath; complete. The flap has three holes, the top corner stitched. Back seam, stitched at 5mm intervals. Tooled decoration. On the front, upper section, running scroll with hatched borders; lower section, a faint three-strand plait. On the back, upper section, a vertical band and three diamond-shaped motifs in a panel; lower section, two vertical lines.”

Dating to the mid 11th century, my sheath is classified as a “B2, winged” type. B2, winged was a new style of sheath that first starts appearing in the 11th century and apparently some of the oldest examples of it were found during the Dublin excavations. This new style was inspired by a combination of sheaths from various cultures present in 10th century Dublin, taking design features from them all in turn. The style was seemingly adopted with gusto by the leatherworkers in Hiberno-Scandivian Dublin and sheaths belonging to this style are found there for another 250 years, even surviving Ireland’s Norman invasion (Cameron, 2007.) B2, winged sheaths are commonly found tooled with decorative abstract designs, my sheath is therefore quite representative of its type.

My version was created several years ago by Merchant of Menace, to accompany a little knife with a bone handle that I use for my day-to-day Viking household tasks. I couldn’t bring my knife along with me to Ireland in my hand luggage, so you shall have to imagine I have it somewhere out of shot. (This is an issue that I am sure would have proved extremely problematic for the early Scandinavians “visiting” the Dublin area in the 9th century, had they travelled via Ryanair longships.)

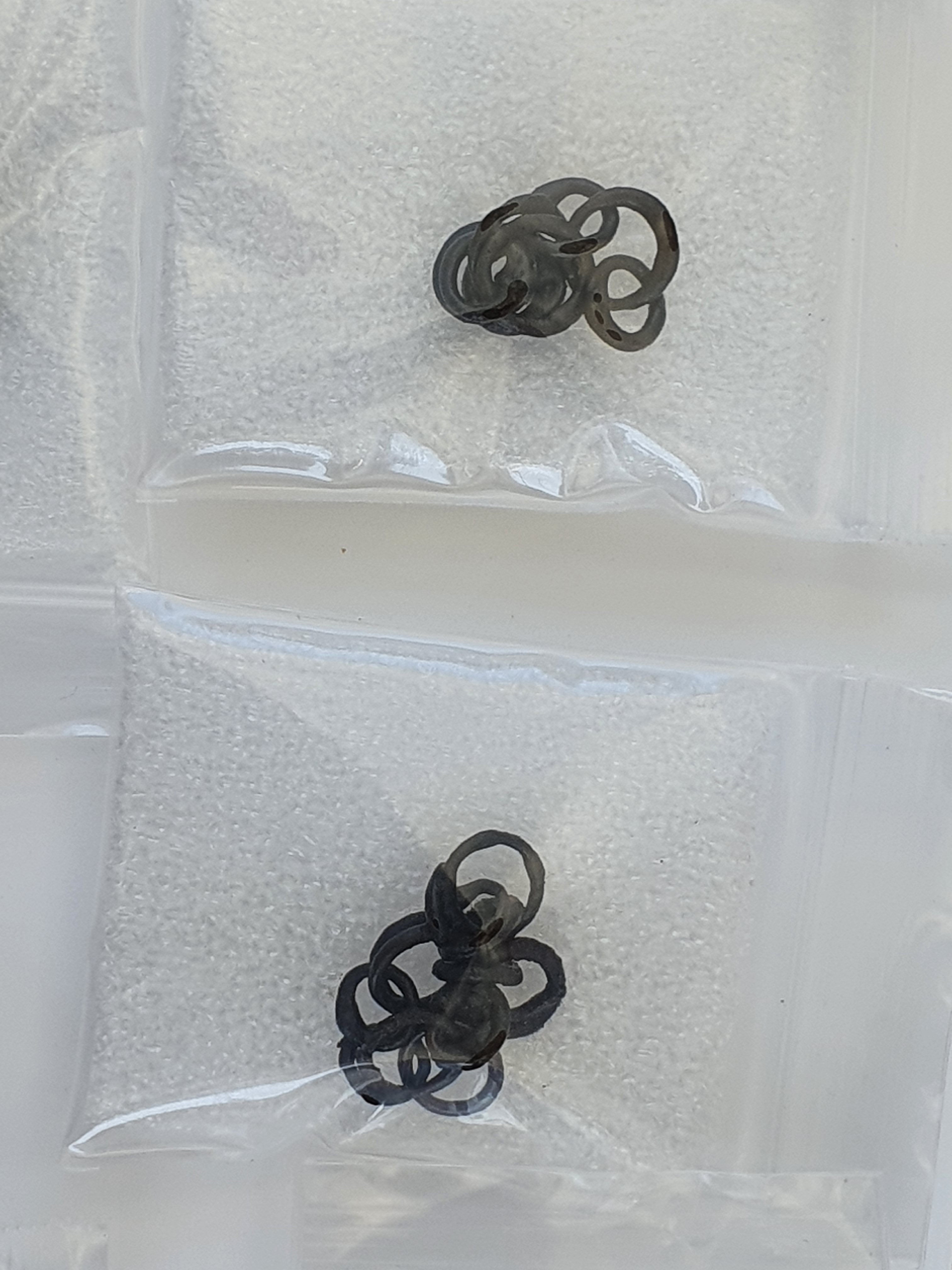

Jet ring (E81:10, E172:10608, etc.) Winetavern Street, Fishamble Street.

Finger rings were found in Dublin, as well as bracelets with a D-cross section that seem to have been popular and many other fragments. The broken and unfinished pieces would provide evidence for jet being worked in the town, after being imported from Whitby. Wallace (2016, p.298) suggests that one possible location for jet working could be in Yard 2 of Fishamble Street, where it is certain that amber was being worked on a commercial level in the Viking Age.

My ring is made from agate instead of jet, as I couldn’t find an affordable jet ring in one piece like this. However, it has the same D-cross section as several of the Dublin rings and is solidly black enough (and light enough in weight) to give the same impression as jet. If I could ever find a piece of jet large enough and a craftsperson willing to make it, I’d love to replace it with a jet or lignite version in the future.

Turned wooden bowl. 11th century, Fishamble Street.

The original was made of alder, whereas mine is of ash. It was made by Waffle and Wood based upon a photo shared by Irish Archaeology.ie. It is not mentioned in Viking-Age Decorated Wood (Lang, 1988), however, this is not unusual- I don’t know of a publicly available exhaustive catalogue of all the wood found in Wood Quay. Turned bowls and cups are commonly found at Early Medieval sites and Dublin is no exception. The fragments of at least 600 turned wooden vessels and 300 cores were found across numerous sites in the town. Wallace (2016, p.251) suggests that the sheer volume of finds would support turned vessels not only being used in the town often but also being produced there too.

Stylistically, the Dublin bowls generally tend to be straight-sided- this bowl does not fit the trend. However, it is decorated on the outside with incised lines, which is a feature seen on other contemporary bowls from the area. The fact that the bowl retained its foot after the turning process is interesting, as they are usually removed. We’re not sure exactly what the bowl was made to contain or if it even had a specific purpose- I used mine to hold some hazelnuts, which were a popular foodstuff in Viking Dublin (Geraghty, 1996.)

I for one would absolutely love some more information on this item from Fishamble Street!

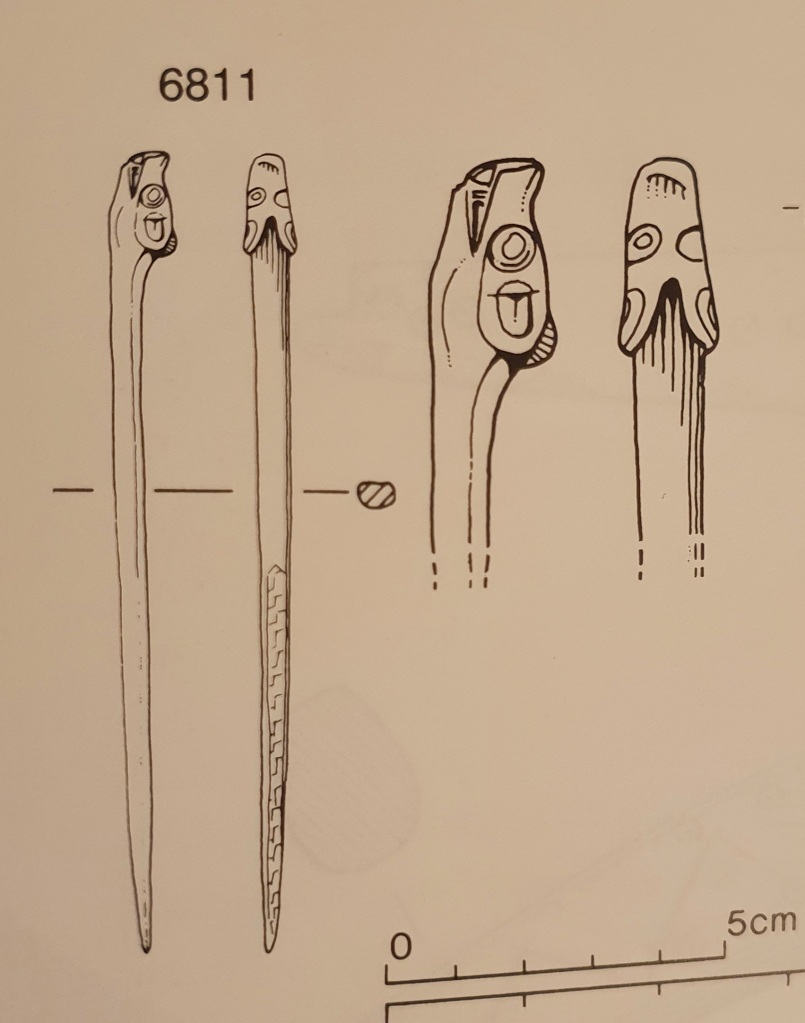

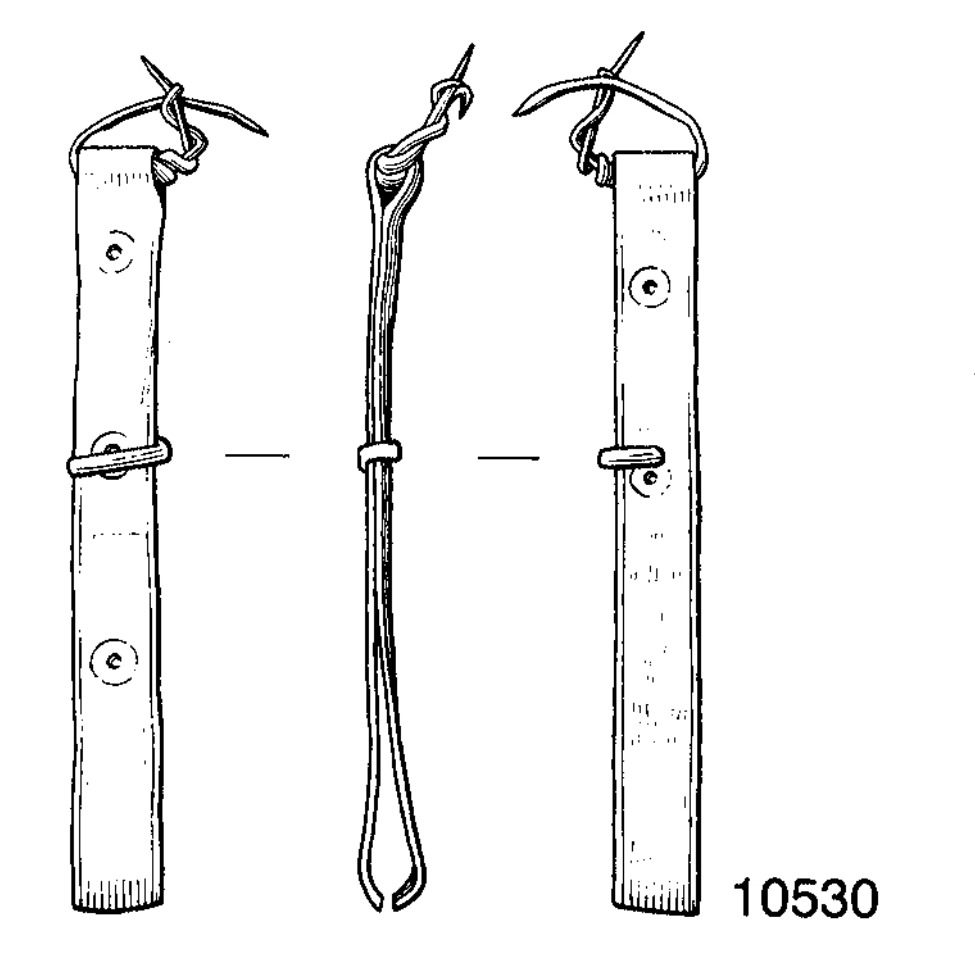

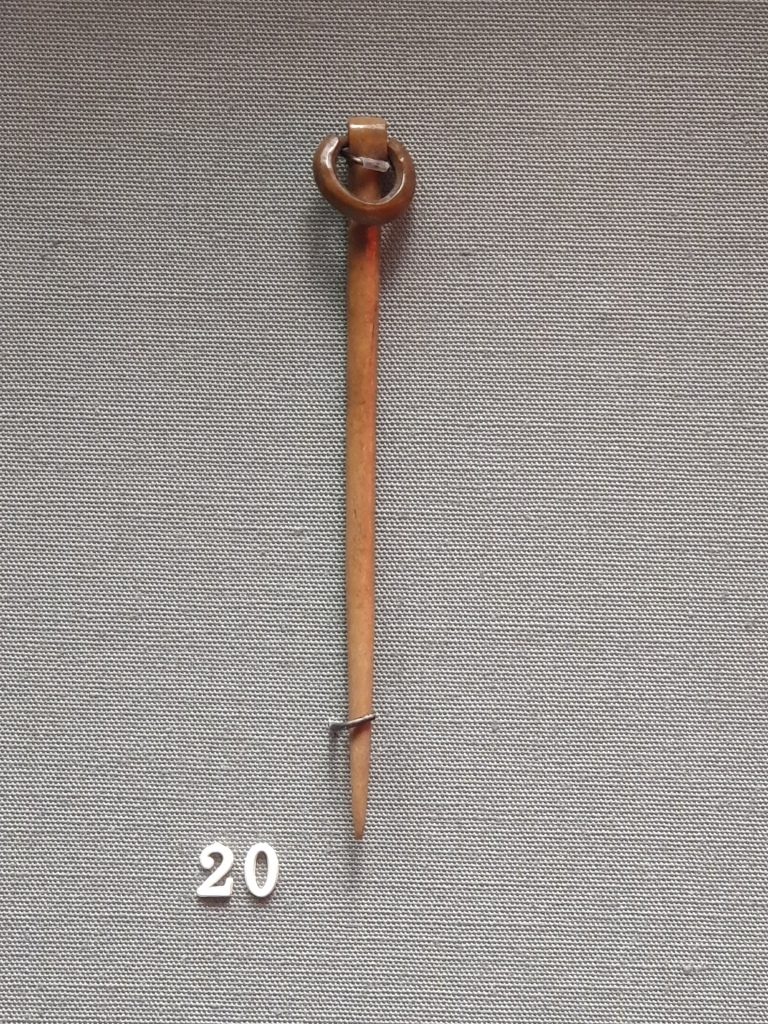

Bone ringed pin (E172:13988.) 945-55AD, Fishamble Street.

Now is my time to admit a small mistake. I’m not sure if it was the wind, the cold or the excitement getting to me, but I somehow got it into my head that the bone ringed pin E172:13988 dated to the 11th century. It does not, it was dated quite concretely using a coin found on its level to 945-55AD- so it would have been more at home perhaps with my 10th century set. Whoops! Then again, ringed pins of this design (albeit in metal) are a Hiberno-Scandinavian specialty that became popular in the 10th century in Dublin and remained so for another 200 years at least (Fanning, 1994.) They are thought to be Irish in origin and adopted into Hiberno-Scandinavian fashion, where they spread in popularity to Britain and Scandinavia. So perhaps, had I worn a metal version of this pin, it wouldn’t be such a mistake after all!

The remarkable and rare thing about E172:13988 is that it is made entirely from bone. My replica (which is highly cherished and only worn this once for the photos!) was made and gifted to me by my friend Peter Merrett. Peter, like the Viking Age craftsman who made the original must have been, is marvellously talented and has decades of experience in boneworking. Despite this, he said that he would not be making any more of these in a hurry, as they are difficult to make and too easy to break. He reckons that E172:13988 may have been a show of skill for the craftsman or perhaps one of those “really good ideas” that you quickly realise is not so good once you start.

Fanning (1994) describes E172:13988 as follows: “Bone. Polished bone shank tapers to fine point. Head is actually perforated in an hourglass fashion but is nicked below to give the impression of being looped, hence skeuomorphic of a metal looped-over pin. The small lozenge-sectioned ring is slightly damaged, with one narrowed end complete. It swivels freely in the pin-head.” (p. 113.)

I had to look up what “skeuomorphic” meant and apparently it means when a thing has a feature that is included to make it look functional, but it’s purely decorative. In the case of E172:13988, that means that the original ring didn’t originally swivel round in the hole of the pin, whereas Peter’s version does (as he is a master of his craft and was able to manage without breaking it!) You learn something every day!

References

Cameron, E. (2007). Scabbards and Sheaths from Viking and Medieval Dublin. Dublin: National Museum of Ireland.

Fanning, T. (1994). Viking Age Ringed Pins from Dublin. Dublin: Royal Irish Academy.

Geraghty, S. (1996). Viking Dublin: Botanical Evidence from Fishamble Street. Dublin: Royal Irish Academy. p.43.

Mainman, A. J. & Rogers, N. S. H. (2000) Craft, Industry and Everyday Life: Finds from Anglo-Scandinavian York. York: Council for British Archaeology. p.2571-2574.

National Museum of Ireland. (1973). Catalogue of Exhibition. Dublin: Department of Education.

Pritchard, F. (1992). Aspects of the Wool Textiles from Viking Age Dublin. In: Bender Jørgensen, L & Munksgaard, E. (Eds). Archaeological Textiles in Northern Europe: Report from the 4th NESAT Symposium. Copenhagen: Det Kongelige Danske Kunstakademi. pp.93-104.

Pritchard, F. (2014). Textiles from Dublin. In: Coleman, N. L. & Løkka, N. (Eds). Kvinner i vikingtid. Oslo: Scandinavian Academic Press. pp.224-240.

Pritchard, F. (2020). Twill Weaves from Viking Age Dublin. In: Bravermanová, M., Březinová, H. & Malcolm-Davies, J. (Eds). Archaeological Textiles – Links Between Past and Present NESAT XIII. Langenweißbach: Verlag Beier & Beran. pp.115-123.

Pritchard, F. (2021). Evidence of tablet weaving in Viking-age Dublin. In: Pritchard, F. (Ed). Crafting Textiles: Tablet Weaving, Sprang, Lace and Other Techniques from the Bronze Age to the Early 17th Century. Oxford: Oxbow Books.

Wallace, P. F. (2016). Viking Dublin: The Wood Quay Excavations. Sallins: Irish Academic Press. pp.251-309.

Walton, P. (1988.) ‘Dyes of the Viking Age: A Summary of Recent Work’, Dyes in History and Archaeology 7th Annual Meeting. York. York: Anglo-Saxon Laboratory. p.14-20. Available at: https://www.aslab.co.uk/app/download/15932285/ASLab+Walton+1988ver2+DHA7+Dyes.pdf

Wincott Heckett, E. (2003) Viking Age Headcoverings from Dublin. Dublin: Royal Irish Academy.

If you liked this article, please consider following my blog for updates when I post. If you really liked it, please consider donating to my Ko-Fi account and help me afford to keep the lights on! You don’t need to make an account and I keep 100% of whatever you decide to tip me.