Note: I wrote the majority of this article in Winter 2020 and have learned a lot more about Viking Age food in the meantime. There are things I would do differently in future and I do plan on repeating this experience again, with more planning. I considered abandoning this article and not publishing, but I thought some folks might appreciate it as it is. I’m also interested in seeing what recommendations (hopefully of a yummy kind) I might get before I try it again.

Food is universal, yet what is eaten in a place or time can tell us so much about the culture or people doing the eating. Mealtimes contribute in large to the structure of our day and many of us get huge enjoyment from them. Food is one of the simple pleasures, after all. Food is also something that can be recreated and experienced, just as our forefathers did. To taste a historical dish made with love and careful attention to remaining evidence is to experience a fleeting sense of time travel.

So, I decided before I even started this blog that I wanted to do something with early Medieval food. I attended an modern training event for re-enactors early last year (blessedly just before Covid really kicked off) as a member of the kitchen crew and I met several excellent living historians with a lot of experience cooking Viking Age food in camp. Conversations with them set me thinking about food and the types of things I’d prepared for camp prior.

I was usually the person who cooked for my group, however, I began to realise that much of my knowledge of food and cookery in period was inherited “re-enactor’s knowledge”. People ate a lot of soup and bread, meat was expensive and everyone drank ale instead of the fetid bacterial soup that sat in wells. While this stuff was not wrong per-se, it was very unspecific. I knew that most vegetables at the time were smaller and far less uniform than the hyper-farmed examples we have today and that their carrots were probably not orange. However, I couldn’t tell you what fruits and vegetables were most commonly grown and I certainly couldn’t describe what material evidence there was at various settlements. How much of all that has survived, let’s say in Anglo-Scandinavian York?

It turns out, quite a bit. We don’t have any recipe books from any Viking Age Gordon Ramsays, but cooking equipment and food waste was found in spades here. By examining the animal remains and traces of vegetal matter left behind, we can form a surprisingly varied diet for the 10th century denizen of Jórvík.

Carolyn Priest-Dorman compiled the following list:

Jorvík [York], Danelaw [England]

- Meat — red deer, beef, mutton/lamb, goat, pork

- Poultry — chicken, geese, duck, golden plover, grey plover, black grouse, wood pigeon, lapwing

- Freshwater fish — pike, roach, rudd, bream, perch

- Saltwater fish — herring, cod, haddock, flat-fish, ling, horse mackerel, smelt

- Estuarine fish — oysters, cockles, mussels, winkles, smelt, eels, salmon

- Dairy products — butter, milk, eggs

- Grains — Oats (Avena sativa L.), wheat, rye, barley

- Legumes — fava (Vicia faba L.)

- Vegetables — carrots, parsnips, turnips (?), celery, spinach, brassicas (cabbage?)

- Fruits — sloes, plums, apples, bilberries, blackberries, raspberries, elderberries (Sambuca nigra)

- Nuts — hazelnuts, walnuts

- Herbs/spices/medicinals — dill, coriander, hops, henbane, agrimony

- Cooking aids — linseed oil, hempseed oil, honey

- Beverages — Rhine wine

I don’t know about you, but I saw this and thought “There’s a lot I can work with there.”

Being in the last week of the second national lockdown and not being one to do things by half, I decided on a week where I would use only foodstuffs from 10th century York. I toyed with the idea of doing a month, but I wasn’t quite that masochistic. This leniency extended to what I drank- I kept drinking water for obvious reasons and I allowed myself my various caffeinated beverages of choice. I didn’t fancy the splitting headaches that would come from going cold turkey and with the low amount of sugar in my 10th century diet, I knew that I would need the pick-me-up.

Furthermore, I must note the additional limitations of this little experiment- I did not pay much attention to seasonality of produce. This is something I would actually like to amend in future with more planning and preparation, however, this was a bit of fun and I just wanted to get stuck in with what I had access to. I also must state that in no way am I trying to claim that my menu is representative of what all Viking Age Yorkies would have eaten regularly, nor that my presentation or ingredient combinations are absolutely accurate. My aim was to educate myself on what foods there is evidence for in York and then to combine them in ways that would allow me to experience the flavour profiles possible with the ingredients available. I had to cook using modern cookware on a modern electric stove, but I did try to use cooking techniques that we have evidence for (e.g. boiling, shallow frying, roasting.) Despite these limitations, I do still believe that my very unscientific endeavour has merit (even if that is only to inspire others to look more into it and because I had fun.)

Day One

I decided to start gently today, with meals that wouldn’t look all that unusual in a modern household. It was mostly a day of prepping, as I had to make all my stocks from scratch for meals throughout the week. Today, I made vegetable stock and boiled a ham for the week.

Brunch: Garlic mushrooms in a cream sauce with flatbread.

The mushrooms were shallow-fried in butter and garlic, with a dash of double cream added at the very end to bind it together and capture all the scrummy pan scrapings. The flatbread was (shamefully) shop-bought and consisted of wheat flour.

Dinner: Carrot and coriander pearl barley “risotto”, topped with cottage cheese.

This was super hearty and had me incredibly full- pearl barley is wondrous stuff. I cooked it slowly using some of the vegetable stock I had made earlier, crammed with lots of other veg (onions, carrots, parsnips, celery.) The cottage cheese added some needed creaminess and the coriander cut through the stodge of it all.

Snacks: Mint herbal tea and a handful of raspberries. I went to bed feeling pretty full.

Tuesday

Breakfast: Oat porridge with dried sour cherries, hazelnuts and rosehip syrup. I made the rosehip syrup myself with only 3 ingredients: local honey, distilled water and rosehips I picked nearby.

It’s nice stuff- I’m not sure if it was the honey I used or the rosehips themselves, but it had a very herbal taste. Almost a bit like old school medicinal drops I used to get as a child! However, it’s far from unpleasant and any sweetness is welcome in the 10thC diet. The porridge was made with oats, water, a little dash of milk and a pinch of salt.

Lunch: Viking Age Ploughmans, bread, cottage cheese, water cress, apple, ham, plum chutney.

For some, cottage cheese is a shuddery horror reminiscent of old-school fad diets. I happen to be quite a fan of the stuff, though it certainly needed the strong flavours of the oniony plum chutney and smokey ham. The water cress was just something I had growing at the time, but it added a nice bit of peppery flavour to the cheese. I was quite surprised how much I enjoyed this lunch, despite it not being my usual mature cheddar and Branston pickle affair.

I’ve eaten variations of this simple meal in encampments across Europe and I suspect that this kind of fare would have been common with working people in the Viking Age, as it was among agricultural workers throughout the centuries since. It would work well with dried meats or fishes instead of ham, as well as substituting the cottage cheese with hard cheese or yoghurts too. Eggs are also a fab addition to a Ploughmans, though I didn’t have one with this meal.

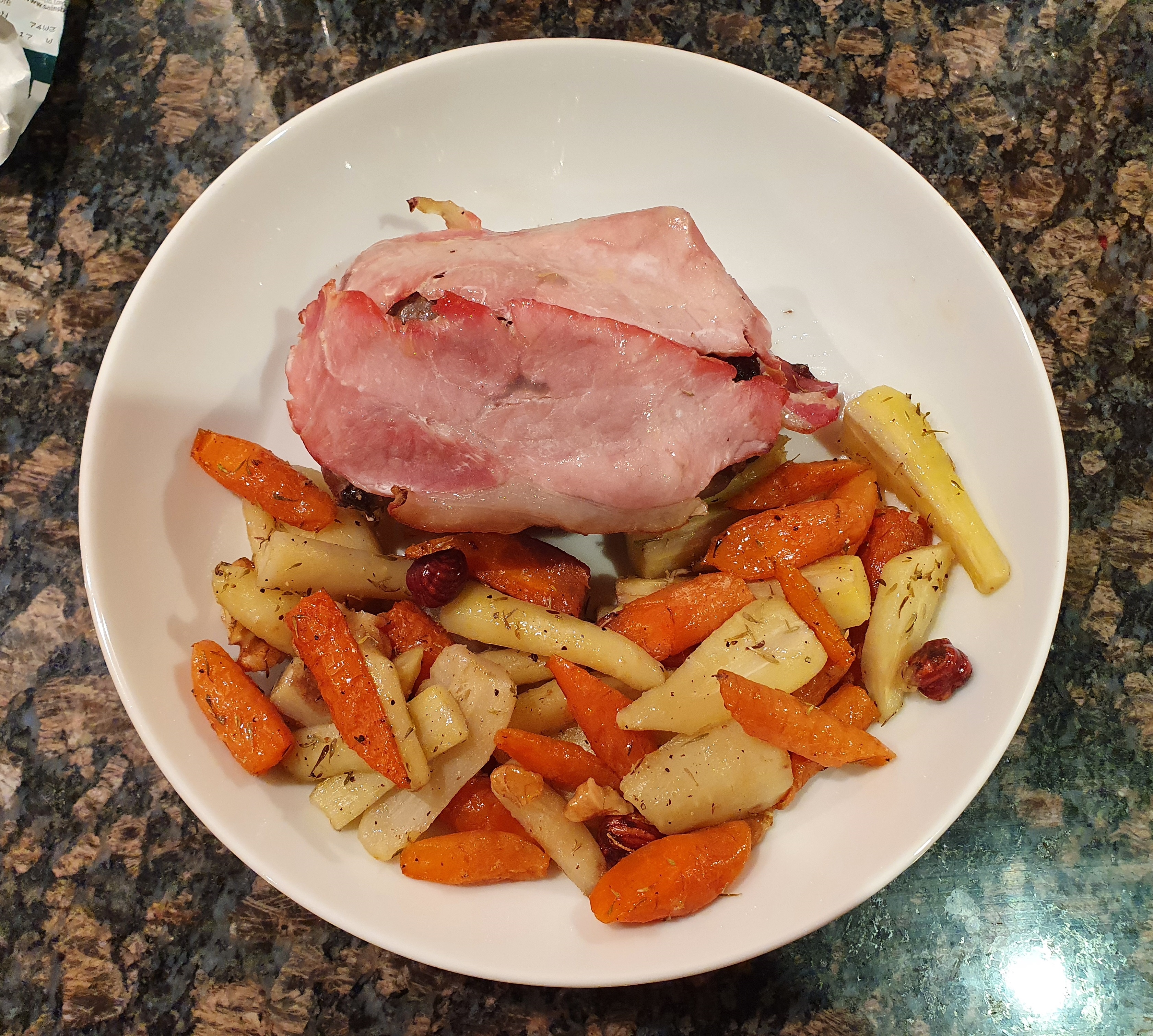

Dinner: Braised beef with garlic, roast parsnips and carrots with thyme.

Again, this dish wouldn’t look that unusual on a modern dinner table. The carrots eaten in 10th century York will have likely born more resemblance to wild carrots than the orange behemoths in supermarkets today. Unfortunately for me, wild carrots are not as common as one might hope in the centre of modern York. I did manage however to bag some gorgeous local-grown, organic heritage carrots- at my local Spar of all places! That all might sound very hipster, but they were teeny, sweet and came in all colours. I boiled them with the parsnips before roasting and actually saved the purple boil water to use for stock later in the week- I think you’ll agree that it was too pretty not to.

Thyme has not been found in the archaeological record in York, however, strains of wild thyme are native to the British Isles. It is also mentioned in 10-11th century English medical text the Lacnunga, under the Old English name “bothen” (Wyrtig, 2015.)

Wednesday

Breakfast: Buttermilk pancakes with rosehip honey syrup, topped with blackberries & double cream.

These pancakes were seriously decadent. I whipped up a huge jug of the batter (with honey in place of sugar) and got to frying up a couple of stacks, one for me, one for Eric and another for a dear friend. My friend and I took ours to go in very modern tupperware, while Eric devoured his at home. We had some errands to run in town that afternoon (the pigeons wouldn’t pick themselves up from the fishmongers, you know), so we had our brunch in a little corner near Coppergate itself.

The pancakes themselves were delicious, but very stodgy. I now know that one probably would have sufficed for me, but apparently that day I woke up and chose violence because we each had a stack of 3, plus cream and fruit. The acidity of the blackberries was welcome to cut through the stodge of the pancake, the cream too provided a necessary moistness and sweetness. Despite my whining though, the cakes themselves were very tasty and fluffy- I can’t be doing with a slimy pancake. Such a dish would have been possible with 10th century food stuffs, but I suspect they would have made their batter without a sweetener and relied on the topping for flavour.

Dinner: Mussels and clams cooked in Rhine wine with garlic, onions and coriander.

This was one of my favourite meals of the week and was pleasingly cheap and easy to make. I was inspired by the steamed mussel dish included in An Early Meal (Serra & Tunberg, 2013), but made some changes to suit my own palate. I adore coriander and I think the lovely green brightened up the seafood, as well as giving it a gorgeous aromatic quality. Clams were also on offer and so in the pot they went. The discarded shells were carefully saved and added to the pan of fish stock I made later that night.

I hadn’t a clue what Rhine wine was before this project, so I looked it up. It turned out that we happened to have some dry white wines that were suitable for this recipe already in our wine cupboard, so I popped open a bottle and tried to imagine what wines from the Rhine might have tasted like 1000 years ago. We happily sopped up the wine sauce with bread after the mussels and clams were demolished.

If you like seafood, you’ll know that steamed mussels are a simple but divine pleasure. The rich marine scent of the mussels, combined with the softened onions, garlic and celery was intoxicating. The white wine just made it *chef’s kiss*.

Snacks: An apple, a hard-boiled egg and handful of blackberries.

Thursday

Lunch: Pan-fried cod fillet on crushed fava beans with mint.

This was one of my favourite meals of the week and let me tell you, I needed it. By Thursday, I was feeling quite sluggish and my appetite was much reduced. I think that this was a combination of all the cooking I was doing (I made all my stocks from scratch and some dishes took a long time to slowly stew away) and the relative lack of sugar. Sure, I was eating a lot of vegetables and some fruit, but it was a lot less than my modern diet. I have quite a sweet tooth and look forward to tea and a chocolate chip shortbread during my work day, as well as pudding after dinner often. Hard-boiled eggs and fruit weren’t cutting it.

I got the cod on offer at one of our local supermarkets and being the Yorkshirewoman I am, I rejoiced. I pan-fried the cod in a little butter, making sure to get the skin all crispy. Meanwhile, I quickly boiled some tinned fava beans, drained and mashed them with some salt, butter and some freshly chopped mint leaves. Placing the cod on a little pile of the crushed beans, I added a little cream to the frying pan and made a quick sauce with the pan scrapings.

Like thyme, mint is a plant that has native strains found in the UK and was used extensively in medicine. I used peppermint as it was what I had access to, but other wild varieties would have been lovely too and would be closer to what could be found in Viking Age hedgerows.

Dinner: Traveller’s Pottage with apples, onions and ham.

This was heavily inspired by a fun video I saw on the Grimfrost YouTube channel. Hanna Thunberg (of An Early Meal authorship) made a simple winter dish that she terms a traveller’s pottage, as it contains ingredients that could be carried in a pack on a journey. Conveniently, it’s also exactly the kind of thing you would want to eat after a long hike. Her version is a Gotlandic twist on it, mine is a York kind of deal.

I made a simple porridge of pearl barley and my purple veg stock (it didn’t stay purple!!), combined with fried spring onions, some of my boiled ham chopped finely and some old apples I’d collected on a walk from Riccall to Stamford Bridge in September. Hanna talks about apples in the video, they will last heroically well if kept somewhere cool, dry and dark. They get sweeter over time and when cooked along with the onions, they really are delicious. I didn’t add hard cheese to mine as I didn’t feel confident in choosing a modern cheese that would be similar to historical examples- maybe in the future, I’ll make my own cheese and use that.

Snacks: Flatbread with cottage cheese and prune chutney, mint tea.

Friday

Breakfast: Buttermilk pancakes with blueberries, double cream drizzle and chopped hazelnuts.

The pancakes returned with a vengeance. As you can see, I learned from my greedy mistake earlier in the week and only cooked one. This time, I topped my pancake with some blueberries that I quickly softened in a hot pan with a little water, as well as some chopped hazelnuts and cream. I liked this better than the fresh blackberries, though the hazelnuts took quite a bit of chewing.

Blueberries are actually a New World plant, but their Old World cousins bilberries were found in York. However, finding dried or even frozen bilberries in November proved an almost Herculean feat. They do grow in the wild, but are not widely commercially available. So, I committed a cardinal authenticity sin and used blueberries.

Dinner: Whitefish soup with cod, carrots, onions and thyme.

This dish was a bit of a trial. I was still feeling very lethargic and not especially hungry, but I had stunk out our entire flat making the fish stock and damn it, Mama didn’t raise a quitter. So, I fried up some remaining cod with some spring onions, celery and carrots, then topped it all up with the fish stock. A dash of cream later made it look a little less dire and more like a New England chowder. The taste was actually really nice and I do think making my own fish stock was worth it- the smell however lingered in the flat for days. This did nothing for my already diminished appetite.

Snacks: Rosehip tea, chopped ham.

Saturday

Breakfast: Hardboiled hen’s eggs, apple and flatbread.

Unfortunately, I didn’t photograph this. You will all have to console yourselves with imagining hardboiled eggs and apple.

Lunch: Kidney and ham soup with carrots, spring onions and ham broth.

I think soldiering on through Friday’s fish trauma may have rekindled my appetite somewhat. Offal can be a divisive foodstuff for some, but I’m quite partial to it! I got some chopped ox kidney from our butchers for pennies and using veg and the broth saved from boiling my ham (with celery, garlic and ground coriander), I was able to make quite a tasty soup.

Animal remains from Anglo-Scandinavian York indicate that when folks did eat meat, they followed the nose to tail approach. Everything remotely edible on an animal was likely eaten. Personally, I believe that much of our modern snobbery and aversion to offal would have been baffling to Early Medieval Yorkies, who will have lived alongside what were essentially open air abattoirs. That is, however, just my view.

Offal generally is extremely high in vitamins and nutrients, which would have been an excellent supplement to a Medieval person’s diet (not that they would have known this.) Ox kidneys are apparently a great source of vitamin B12, selenium and riboflavin– which among other benefits, boost the immune system and reduce fatigue. Yet, here we are mostly putting them in dog food!

Dinner: Wood pigeon topped with bacon and stewed apple, stuffed with hazelnuts, walnuts and prune chutney. Served with roast mixed veg.

This is another dish that sounds quite posh, like something on the menu of a countryside pub with notions (you know the type I mean.) I had to ask around about where to get wood pigeons, as my grandparents didn’t have any in the freezer and they’re not exactly a common site at the big supermarkets. My grandad, who is a canny countryside gent, suggested that I go ask at the fishmongers on Market Street. I thought he was taking the piss at first- “Oh aye?” “Aye,” he said, so off I went.

Turns out he was right and the fishmongers really do stock wood pigeons, when they can get them. You heard it here first. Quite delighted, I ordered a couple and got some venison while I was at it (naturally, at a fishmongers.)

I roasted my prize bird and stuffed it carefully with the nuts and thick spoonfuls of plum chutney I made earlier in the week. The plum chutney really was gratifyingly easy to make and I think it would be even nicer if using spices and proper onions rather than spring onions. The secret is to use dried plums of the kind that would have been imported into Viking Age York- it makes for a much jammier chutney than fresh plums.

Regarding the pigeon itself, it wasn’t for me. The actual taste of the meat was gamey and almost bitter to my palate, thankfully Eric found it much more to his taste. The chutney and nut stuffing I was fond of, as well as the parsnips and carrots I roasted with the bird.

Snacks: Milk, dried sour cherries, mint tea with honey.

I’ve always been fond of mint tea anyway, but even more so when sweetness is limited. Aromatic herbal flavours seemed a lot more intense to me when I wasn’t eating so much processed sugar.

Sunday

Breakfast: Scrambled eggs with spinach, on toast.

Just as it says on the tin, really. I did cheat somewhat and serve my hen’s eggs and spinach on top of regular sliced wheat bread- sue me. It was a Sunday, my entire home smelled of fish and if you’d asked me to bake a loaf or fry some griddle breads, I’d have strangled you.

Spinach is something I eat regularly in my modern diet, so I didn’t feel like eating it up until the end of the week. Leafy green vegetables like spinach would probably have featured prominently in the yards of Jorvík inhabitants, as they grow well year-round and are incredibly nutrient dense. To quickly wilt spinach with a little garlic and toss them with eggs seems as plausible a way to eat it as any, though I may be biased as this is how I often enjoy it in the 21st century.

Dinner: Braised venison with blackberries and dried sour cherries, with veg (onions, garlic, celery, carrots, parsnips and pigeon stock.)

This was a special dish to end the week. I slowly braised the chopped venison steak over a low heat, adding dried sour cherries and fresh blackberries along with stock I made from the pigeon bones. The dried berries soaked up all the savoury stock and cooking juices from the venison, while imparting a woody sweetness to the dish. It went perfectly with the mixed veg I roasted alongside the meat.

This might have been quite a posh dish in period, with venison being a hunted meat and the dried cherries being imported from the continent. It certainly tasted decadent and I’d say that this is one of the dishes I would definitely make again, perhaps if friends came over to feast.

Closing note

This was most certainly a week. Despite frying everything in oil and butter, I actually lost 4lbs. I believe that this was due to my lack of appetite and most importantly due to cutting out much of the sugar in my diet. Weight loss was absolutely not my intention, but I’d be interested to see what would happen if I followed this kind of diet for a month instead. The lack of sugar had me feeling fatigued and generally pretty crappy for much of the week, but I think this would lessen if I’d have continued.

I found that my diet was pretty varied despite being (mostly) limited to the list above. Of course, it is important to remember that most Viking Age people would have eaten much of the same things most of the time, dependent on the season. It is a virtue of the modern age oft taken for granted that we can open the fridge and say “Huh, yesterday I had BBQ ribs, corn and mashed potatoes. I think today I’ll have a chicken dhansak.” This is a luxury that the huge majority of Early Medieval people simply didn’t have. They had the same kind of ingredients available to them during a given season and if they were lucky, they might zhuzh up a meal with the addition of a little something-something they caught or preserved earlier in the year.

The variety in my diet was a result of modern availability of foodstuffs year round and of refrigeration. Had I stuck to a week of bread and vegetable pottage with grains however, I doubt many of you would have found it all that interesting (the flatulence would have been astronomical, though.)

If I do repeat this week in the future, there’s quite a few ingredients that I didn’t get chance to use- these will come centre stage next time. I also avoided baking my own bread- I absolutely loathe making bread, but it would have no doubt been an essential part of most Medieval women’s day. So, I should probably make more of an effort to get my bake on next time! I’ll pay better attention to seasonality too. For now however, I am enjoying being able to indulge in spices, potatoes, chocolate and hot sauce. Not necessarily all at once.

References

Grimfrost. (2020). Viking Age food and cooking. [online video] Available at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Io18i6Pfq_g. Last accessed 17th Jun 2021.

Priest-Dorman, C. (1999). Archaeological Finds of Ninth- and Tenth-Century Viking Foodstuffs. Available: https://www.cs.vassar.edu/~capriest/vikfood.html. Last accessed 17th Jun 2021.

Serra, D & Tunberg, H (2013). An Early Meal – a Viking Age Cookbook & Culinary Odyssey. Furulund, Sweden: Chronocopia Publishing. p1-192.

Wyrtig. (2015). The Lacnunga. Available: https://wyrtig.com/EarlyPlants/LacnungaPlants.htm. Last accessed 17th Jun 2021.

Bibliography

https://www.checkyourfood.com/ingredients/ingredient/716/ox-kidneys